Late last November at the Court of Appeal in London, Lord Justice Arnold made a significant ruling on copyright and the threshold of originality in UK law, in the case THJ v Sheridan1. Although the case concerned the copyright protection of graphical user interfaces (GUIs), its impact is likely to be felt in other categories. This post examines the implications of THJ v Sheridanfor copyright policy at UK cultural institutions.

From ‘skill and labour’ to ‘free and creative choices’

Historically, English copyright law had a low bar for originality, defined by ‘sufficient skill, labour, or effort’. But this has changed in recent decades. The Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) jurisprudence has significantly altered the threshold for originality, and the Court’s influence persists in the UK, even after Brexit.

As Eleonora Rosati, Professor of Intellectual Property Law at Stockholm University, stated in the The IPKat2:

The consistent and abundant string of CJEU decisions on originality have clarified that the EU standard of ‘author’s own intellectual creation’ does require more than simple ‘skill, labour or effort’: a work is protectable if it is the result of ‘creative freedom’ and ‘free and creative choices’ and ultimately carries the ‘personal touch’ of the author.”

Arnold LJ underlined this standard explicitly in his THJ v Sheridanruling:

What is required is that the author was able to express their creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices so as to stamp the work created with their personal touch […] This criterion is not satisfied where the content of the work is dictated by technical considerations, rules or other constraints which leave no room for creative freedom.”

What does this mean for the copyright policies of cultural institutions in the UK?

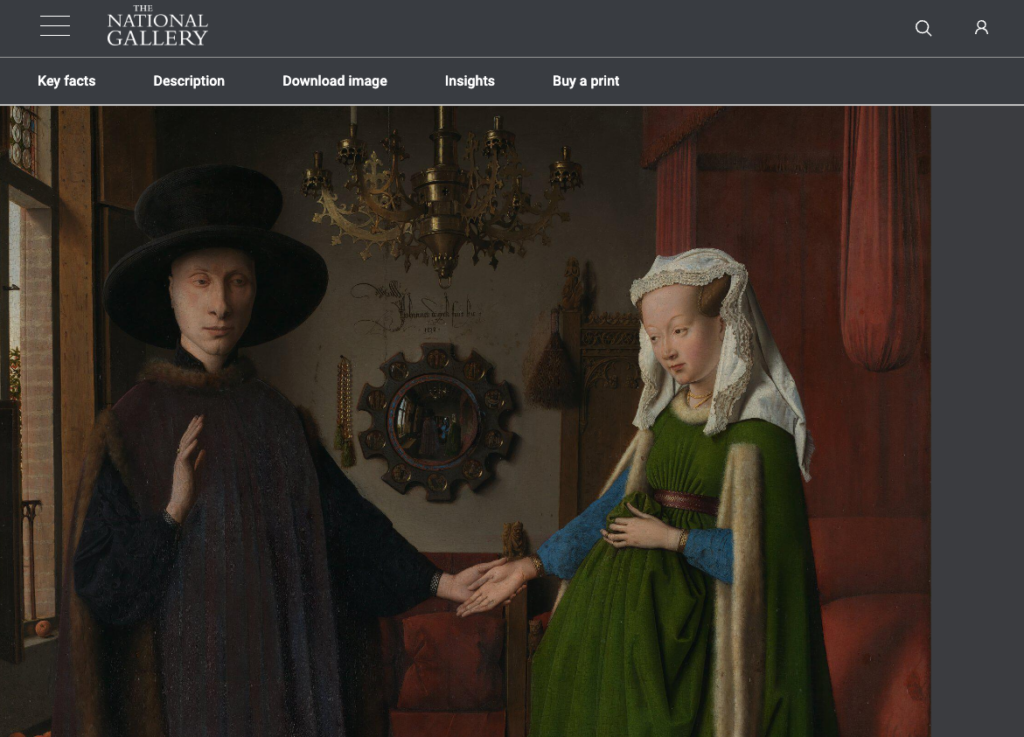

The overwhelming majority of galleries, libraries, archives and museums3 in the UK which have digitised out of copyright works in their collections claim copyright in the resulting digital surrogates. Here is an example at The National Gallery:

The Gallery has asserted copyright in its straightforward digital reproduction of The Arnolfini Portrait,painted 590 years ago by Jan van Eyck. This claim – typical of cultural institutions in the UK, large and small – relies on the outdated ‘skill and labour, or effort’ credo. THJ v Sheridanreaffirms, however, that the ‘free and creative choices’ threshold of originality is the relevant one for modern UK copyright law – as has been repeatedly shown in case law stretching back to Infopaq4 in 2009. Reader, do you discern any evident creative freedom, or free and creative choices, in the Gallery’s digital image?

Arnold LJ’s ruling underscores the falsity of the ‘skill and labour, or effort’ basis on which so many UK museums have – and continue to – assert copyright in simple reproductions of 2D public domain works. To quote Professor Rosati again, “Technically, this has been wrong for ten-plus years.”.

What’s going to happen next?

In the wake of THJ v Sheridan, one can easily imagine a flurry of messages flying between worried rights managers at UK museums, asking what the ruling meant and how others might respond. So, how will institutions react and what changes might we see?

If this ruling finally persuades museums that their copyright assertions are no longer credible, we can expect museum copyright policies to change. Lawyers will be consulted and the Terms of Use of museum websites will slowly be updated. Those ubiquitous ‘© Museum’ statements in credit lines under public domain artworks may quietly vanish. Would the disappearance of image copyright make it easier or cheaper to acquire and reproduce images from cultural institutions? Not necessarily.

Goodbye copyright law, hello contract law?

I anticipate that THJ v Sheridan will accelerate the existing trend towards contract law replacing copyright law as a means of controlling access to public domain collections. If this happens, one shouldn’t assume that access policies will become any more open – the old status quo may simply persist in new form.

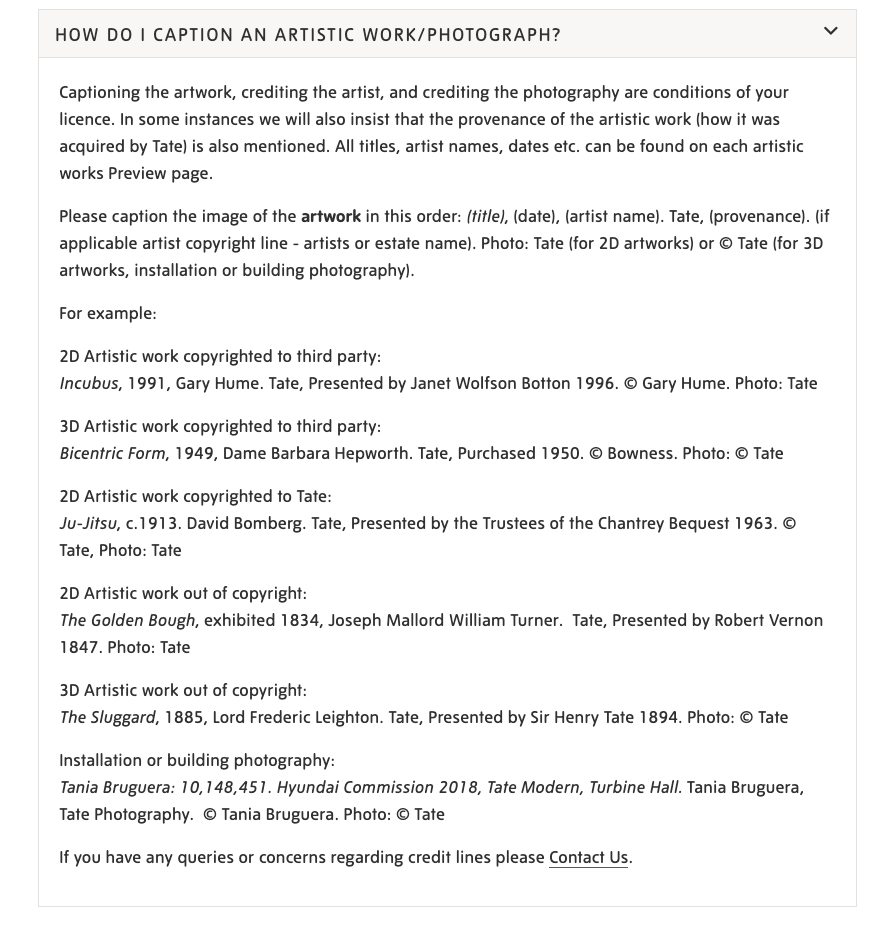

The model of restricted access to digitised public domain works, governed by contract law, has been around for some time. It is, to take one example, practised by Tate Images, enabling Tate to charge fees (on the usual sliding scale of cost, based on the scope and scale of intended reproduction) for licensing images without copyright.

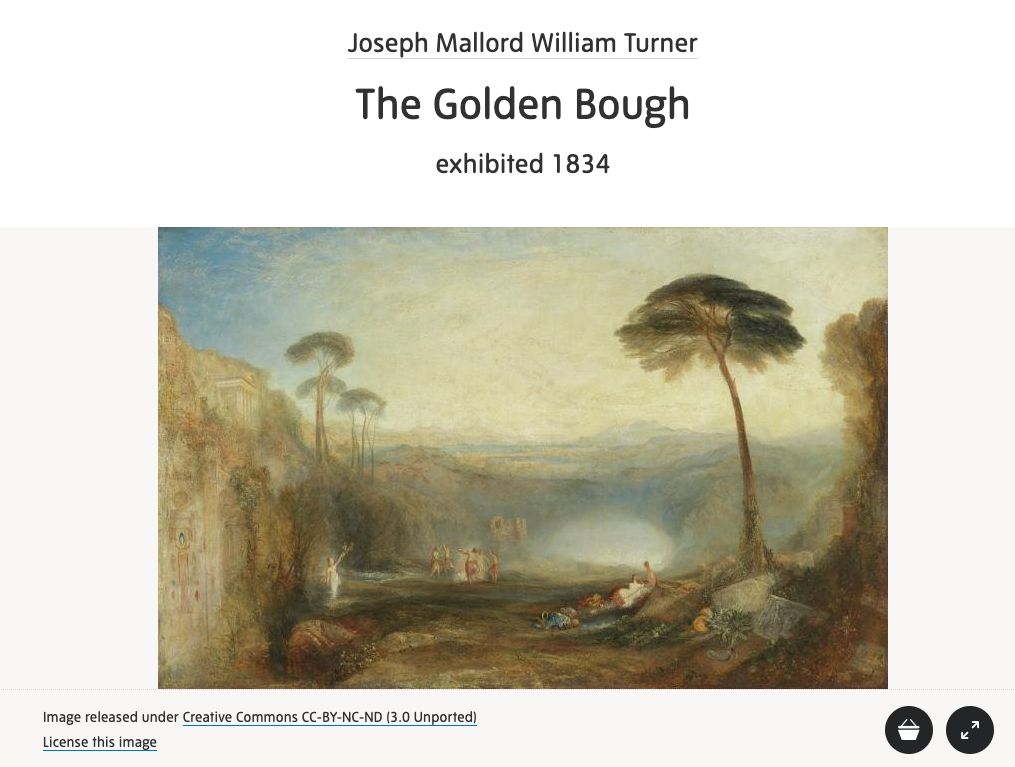

A curious detail here is that on Tate’s main website tate.org.uk, ‘2D Artistic work out of copyright’ images like Turner’s The Golden Bough – used as an example credit line on the FAQs page shown above – are marked with the Creative Commons licence CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported).

Creative Commons’s guidance5 states that to use a CC licence:

You must own or control copyright in the work. Only the copyright holder or someone with express permission from the copyright holder can apply a CC licence or CC0 to a copyrighted work.”

Assuming that Tate follows this guidance, one must conclude Tate has claimed copyright in the Turner image, which seems anomalous from the information presented on the Tate Images website. If anyone can clarify this conundrum, please get in touch.)

Using contract law enables Tate to administer its digital images of public domain works on the gallery’s own terms, to manage and monetise their circulation and reproduction. It seems likely that UK museums which have hitherto relied on copyright law may consider adopting Tate’s contract law-centred approach in the months to come.

What does it all mean?

THJ v Sheridan has profound implications for copyright policies in UK cultural institutions. By reaffirming the shift from the old ‘skill and labour’ basis for originality to the modern standard that requires visible ‘free and creative choices’, it challenges the longstanding practice of museums claiming copyright in digital surrogates of 2D public domain works. In response, cultural institutions may need to update their copyright policies and consider using contract law more fully to control access to their collections – should they wish to continue doing so.

UK cultural institutions play a crucial role in safeguarding a vast repository of public domain works. Consequently, the ways in which they grant access to their digitised collections really matters. Will THJ v Sheridan expedite the implementation of more open and inclusive access policies in museums, or will the current state of affairs remain essentially unchanged? It should be fascinating to watch.

Footnotes

- THJ Systems Limited & Anor v Daniel Sheridan & Anor [2023] EWCA Civ 1354, https://caselaw.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ewca/civ/2023/1354 ↩︎

- ‘Originality in copyright law: An objective test without any artistic merit requirement, recalls Arnold LJ’, Eleonora Rosati, IP Kat, 30 November 2023, https://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2023/11/originality-in-copyright-law-objective.html ↩︎

- A Culture of Copyright: A scoping study on open access to digital cultural heritage collections in the UK. (Towards A National Collection). Andrea Wallace, 2022. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6242611 ↩︎

- C-5/08 Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62008CJ0005 ↩︎

- About CC licenses, https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/ ↩︎

Suggested further reading

- Originality in copyright – a review of THJ v Sheridan, James Tumbridge and Benedict Sharrock-Harris, 6 December 2023, https://www.vennershipley.com/insights-events/originality-in-copyright-a-review-of-thj-v-sheridan/

- Open GLAM survey, Douglas McCarthy and Andrea Wallace, 2018-, https://douglasmccarthy.com/projects/open-glam-survey/

- Surrogate Intellectual Property Rights in the Cultural Sector (2022). Andrea Wallace, 2023 Journal of Law, Technology and Policy 303, https://ssrn-com.tudelft.idm.oclc.org/abstract=4323691

A version of this post was originally published on the Copyright Literacy website.

© Douglas McCarthy, 2024. Unless indicated otherwise for specific images, this article is licensed for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Please note that this licence does not apply to any images. Those specific items may be re-used as indicated in the image rights statement within each slide. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt this article, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence, indicate if changes were made, and abide by the other licence terms.

The contents of this article are not legal advice and cannot be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice should be sought on a case-by-case basis.

Citation

McCarthy, D. (2024). After THJ v Sheridan. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13371597