Is it possible for the same digitised public domain work by the same artist to be considered both in and out of copyright by different museums within the same legal jurisdiction? The answer is yes.

In this post, I explore this conundrum by examining the copyright and licensing policies of major UK museums. I outline the legal context and show how UK museums often use copyright claims and restrictive licensing practices to severely limit the reuse of digitised public domain collections.

Intellectual creation means more than skill, labour or effort

Despite recent developments in copyright law and abundant evidence of the benefits of open access, many UK museums continue to assert copyright in digital reproductions of public domain works in their collections.

Lord Justice Arnold’s ruling in THJ v Sheridan (2023) reaffirmed that the “free and creative choices” threshold of originality is the relevant standard for modern UK copyright law. It echoed the Intellectual Property Office’s existing position that:

Simply creating a copy of an image won’t result in a new copyright in the new item. According to established case law, the courts have said that copyright can only subsist in subject matter that is original in the sense that it is the author’s own ‘intellectual creation.”

Intellectual Property Office, ‘Copyright notice: digital images, photographs and the internet‘, updated 4 January 2021

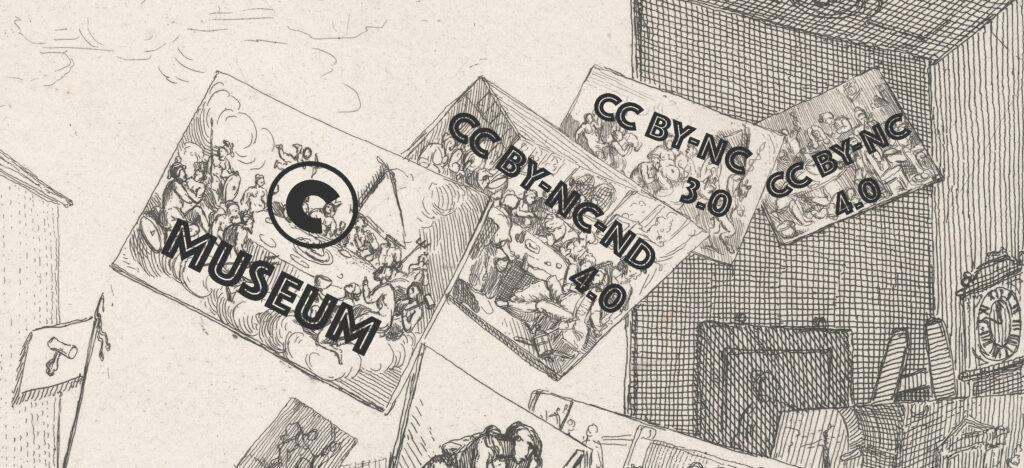

Despite this, many UK museums still claim copyright in simple reproductions of 2D public domain works. This becomes even more problematic when museums apply Creative Commons (CC) licences to these digital reproductions.

Why is this problematic?

Creative Commons’ own guidance states that to use a CC licence:

You must own or control copyright in the work. Only the copyright holder or someone with express permission from the copyright holder can apply a CC licence or CC0 to a copyrighted work.”

Creative Commons, ‘About CC licenses‘

Applying CC licences to images without copyright is misguided and inappropriate, yet it is common practice at memory institutions – even when museums don’t claim copyright. Many of the UK’s largest cultural institutions use CC licences with non-commercial (NC) and/or no-derivative (ND) stipulations, greatly restricting how digital content can be reused.

What does this look like in practice?

Let’s look at some examples, noting the copyright claim and applied CC licence in each case:

British Museum

Attributed to Dorothea Graff, after Maria Sibylla Merian

© The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

National Gallery

© The National Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

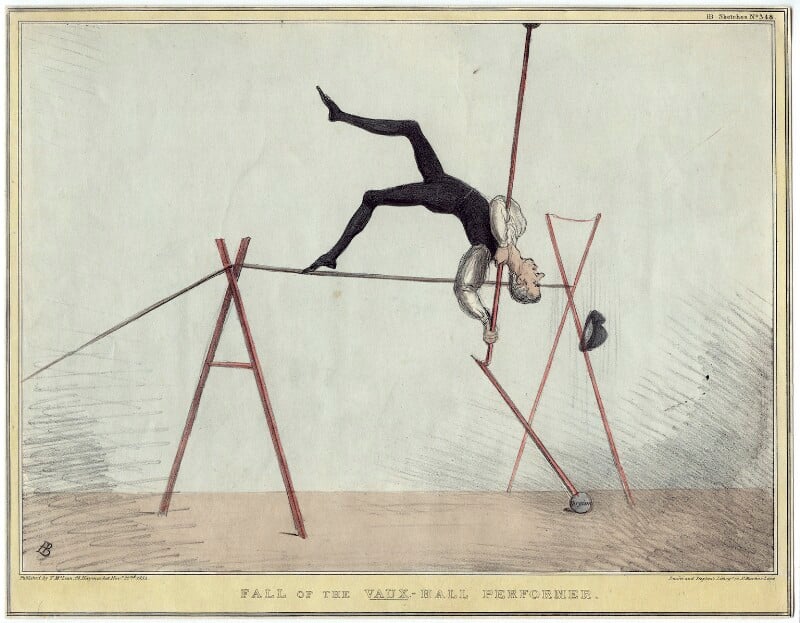

National Portrait Gallery (NPG)

© National Portrait Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

(Note that the National Portrait Gallery uses a deprecated CC licence version. Version 3.0 CC licences were replaced by version 4.0 licences in November 2013.)

The National Portrait Gallery uniquely offers ‘Professional,’ ‘Academic,’ and ‘Creative Commons’ licences, each with different image sizes, usage scenarios, and fee structures.

The ‘Creative Commons’ option for limited non-commercial use solicits donations from users and requires sharing personal data (an email address) to access and download a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 licensed low-resolution image.

Science Museum Group

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

National Galleries Scotland (NGS)

National Galleries Scotland. CC-BY-NC 3.0

Like the National Portrait Gallery, National Galleries Scotland also uses old version 3.0 CC licences.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Responding to a recent Freedom of Information (FOI) request about its copyright policy, a NGS spokesperson stated:

NGS does not claim copyright on digital images of artworks that are out of copyright.

All images on our website of works that are out of copyright have the caption Creative Commons CC by NC [sic] and no additional copyright line.“

This application of CC licences to works where NGS does not claim copyright is deeply odd and a clear misuse of Creative Commons licensing.

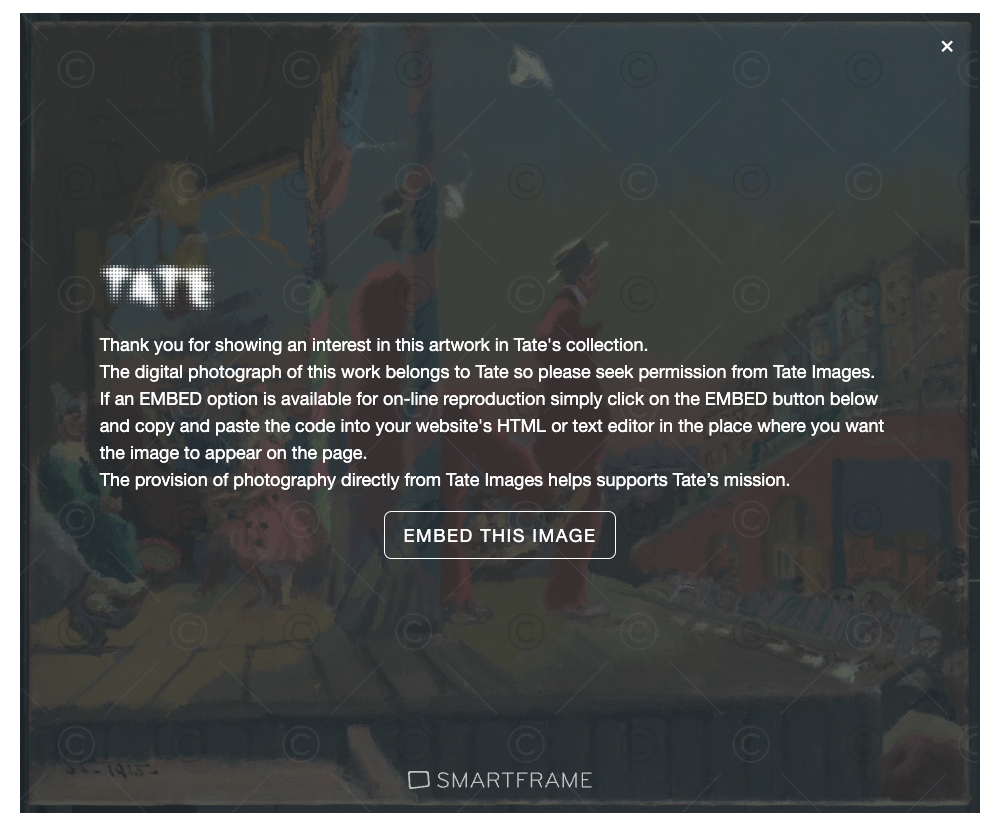

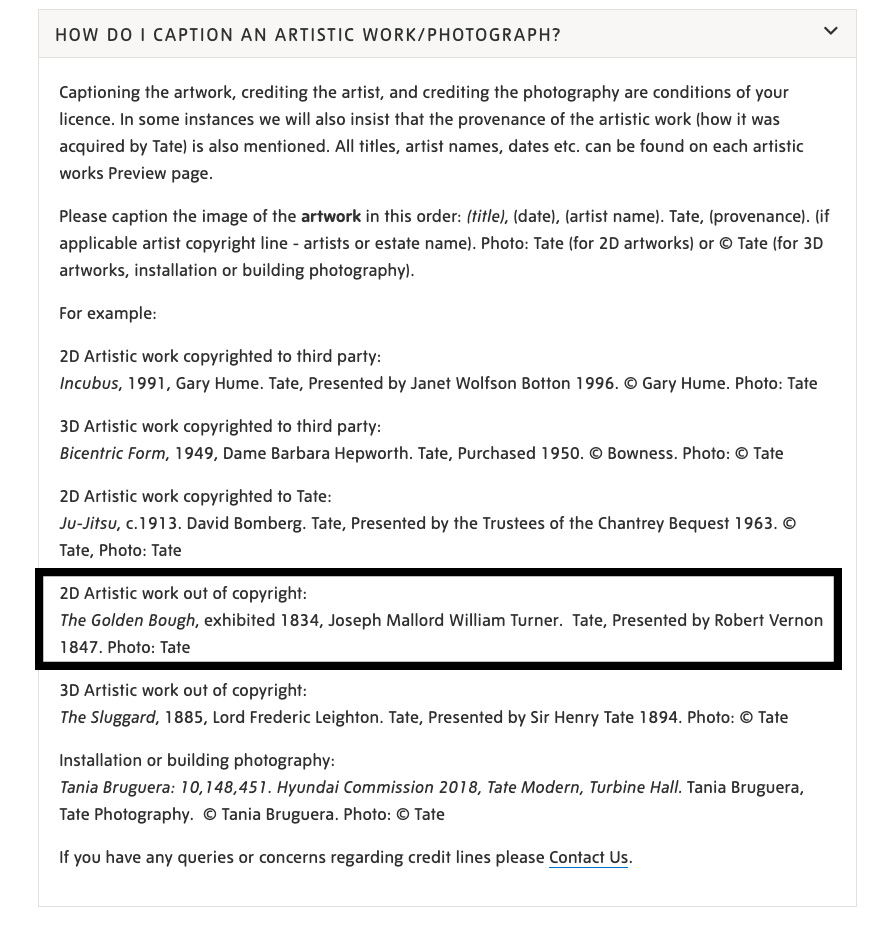

Tate

Tate’s copyright policy and licensing practice across its main collections websites (tate.org.uk and tate- images.com) seems inconsistent and a little opaque. Let’s examine this using Brighton Pierrots by Walter Sickert (1860-1942) as a sample.

Tate.org.uk (shown above) states that the online image is ‘released under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED’, implying that Tate claims copyright in its digital surrogate of this public domain work.

The same painting on the Tate Images website is not accompanied by a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence, nor is there a clear copyright statement:

Additionally, Tate deploys technical protection measures on Tate Images to watermark images and prevent ‘right click’ saving by users. Note also the suggestive and repeated pattern of a copyright symbol within the digital watermark.

Does Tate claim copyright in this artwork, and others like it? It’s not clear. Tate’s model caption for a ‘2D Artistic work out of copyright’ (highlighted below) does not include a copyright symbol.

Copyright policy in a closed box?

As these examples demonstrate, many of the UK’s largest and most important museums claim copyright in digitised public domain works and use restrictive licensing to prevent their free circulation and reuse. But these copyright claims are no longer supported in law. Why do many museums seem to operate in a policy vacuum, ignoring relevant legal developments and making their own free and creative choices about copyright?

Dr Andrea Wallace’s extensive 2022 report ‘A Culture of Copyright’, commissioned by the Towards a National Collection programme, stated:

… there is no consensus in the UK GLAM sector on what open access means, or should mean. There is also a fundamental misunderstanding of what the public domain is, includes and should include.

Andrea Wallace, ‘A Culture of Copyright: A scoping study on open access to digital cultural heritage collections in the UK’ (Towards A National Collection, 2022), CC BY, https://zenodo.org/records/6242611

A lack of expertise and resources around copyright at museums certainly accounts for much of this confusion. Further clues as to why policy and practice are stuck in the doldrums are contained in museums’ responses to FOI requests. In 2018-19 several UK museums were asked: ’What, if any, legal advice is your institution operating on with regards to licensing images of public domain artworks in your collection?‘

Here’s what they said.

National Gallery: ‘We rely on our own interpretation of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.’

National Galleries Scotland: ‘We seek advice from sister institutions, copyright lawyers, and copyright consultants via various heritage forums, such as the Museums Copyright Group, who provides assistance with Intellectual Property Advice.’

When asked recently if it has sought or received any legal advice on copyright in its digital images of out-of-copyright artworks in the last ten years; National Galleries Scotland replied in the negative.

Tate: ‘We operate on no specific legal advice, but rather our interpretation of the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.’

Victoria & Albert Museum: ‘The V&A has not taken any legal advice on the licensing of images of public domain works for which it owns copyright. We rely on our own interpretation of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.’

Wallace Collection: ‘There has been no recent legal advice sought on licensing images of public domain artworks in our collection.’

(The National Portrait Gallery and Sir John Sloane’s Museum declined to answer.)

These responses suggest that policy makers at UK museums determine copyright and licensing policies on their own terms, regardless of important legal developments such as Infopaq in 2009, subsequent jurisprudence at The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), and domestic case law such as THJ v Sheridan.

A sense of “business as usual” was conveyed by a Tate spokesperson when quoted recently in Museums Journal:

We haven’t made any changes since the ruling [THJ v Sheridan]. Our picture library continues to charge reproduction fees for supplying high-resolution images, as it has for years. These are different to copyright fees, which we only charge if the artist (or estate) has transferred the copyright of that artwork to Tate or appointed Tate as their copyright agent.

We do license low-resolution images for some purposes without charge – including some copyright-protected images and archive items under Creative Commons licences, for example – but we have done this for years, so it isn’t a result of the ruling.

‘Keeping an open mind on copyright‘ by Geraldine Kendall Adams, Museums Journal, 28 May 2024

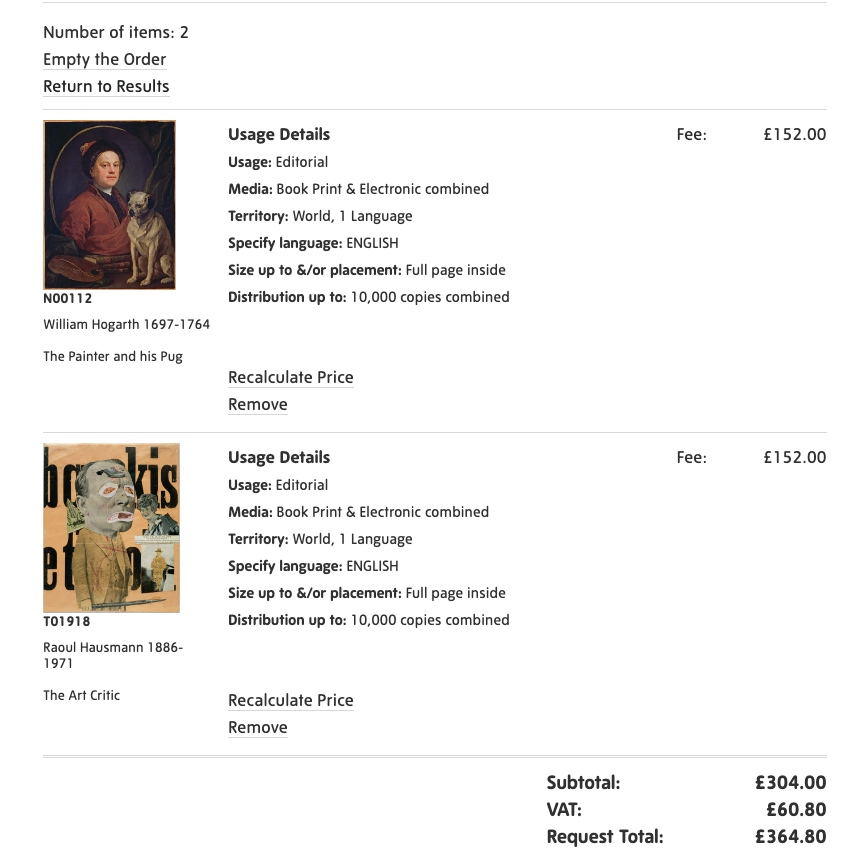

What, one might ask, is the difference between Tate’s ‘reproduction’ and ‘copyright’ fees? To find out, I selected one out-of-copyright image (Hogarth) and one in-copyright image (Hausmann) and entered a commonplace editorial usage into the Tate Images price calculator. The fee was the same for both images, £152.00 excl. VAT:

As I wrote recently, it would not be surprising if UK museums that have relied on copyright law for years to control (and attempt to monetise – usually without success) began pivoting towards Tate’s contract law-centred approach. This would be an attempt to preserve the closed access status quo – administering digital images of public domain works on institutions’ own terms, rather than openly and in the public interest.

Schrödinger’s copyright

Outdated interpretations of copyright law, restrictive reuse policies, technical protection measures, and inappropriate use of Creative Commons licences are frustrating access to public domain heritage in UK museums. This leads to a bizarre situation we might call ‘Schrödinger’s copyright,’ where the same artwork by the same artist is labelled ‘in copyright’ by one museum and ‘public domain’ by another – simultaneously – echoing Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment.

Cultural institutions are custodians of large and important repositories of public domain works. Their public missions matter, as do the ways they provide access to their collections. The opportunity cost of restrictive practices is vast—many missed chances to reach, inform, and engage people with cultural heritage. Open access remains ‘a road not taken’ for many UK museums.

Some hope that THJ v Sheridan will inspire more open policy making in UK museums, which is long overdue. Are museums motivated and resourced to do so, or are they mired in the unsatisfactory status quo? We shall see.

© Douglas McCarthy, 2022. Unless indicated otherwise for specific images, this article is licensed for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Please note that this licence does not apply to any images. Those specific items may be re-used as indicated in the image rights statement within each slide. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt this article, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence, indicate if changes were made, and abide by the other licence terms.

The contents of this article are not legal advice and cannot be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice should be sought on a case-by-case basis.

Citation

McCarthy, D. (2024). Schrödinger’s Copyright. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13371375