The choices that museums make about copyright and licensing as they digitise their collections have profound implications for public access. In an era where digital technologies are opening up heritage like never before, are some of our cultural institutions becoming gatekeepers?

In a series of articles this year, I’ve been analysing copyright and licensing practices at UK museums. In the process, I’ve pinpointed some troubling trends concerning digitised public domain collections. In ‘After THJ v Sheridan’ and ‘Schrödinger’s Copyright’, I critically examined the legal foundations of institutional copyright claims and highlighted the misuse of Creative Commons licences. My most recent article ‘Balancing Access and Income’ discussed the trade-offs inherent in the traditional picture library model, and shared data on its often modest profitability.

Today, I examine how London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) manages copyright for its digitised public domain collections. My analysis is based on a detailed review of the V&A’s online platforms, supported by data obtained through Freedom of Information requests.

Sustaining the V&A: Funding, income, and legal obligations

Founded in 1852, the Victoria and Albert Museum is a preeminent institution dedicated to art, design, and performance. Its collections, numbering 2.7 million objects, span 5,000 years of art from cultures across Europe, North America, Asia, and North Africa. The V&A’s mission is to “champion design and creativity in all its forms, advance cultural knowledge, and inspire makers, creators, and innovators everywhere.”1

The V&A relies on government funding for between one-half to two-thirds of its income. Between 2008 and 2023, the museum received over £725 million in Grant-in-Aid funding from the UK’s Department for Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS). While such substantial public funding underscores UK museums’ responsibility to serve the public interest by ensuring that collections are preserved and accessible, it should be noted that Grant-in-Aid imposes legal obligations on institutions to maximise opportunities for self-generated income. The need to generate income became more urgent in 2010 with the change of government in the UK. After that, Grant-in-Aid to the V&A steadily declined in real terms over the following decade.2

The V&A has a long history of monetising its collections. The then South Kensington Museum was one of the first institutions to recognise the value of producing and selling surrogates of its collections, and photographic reproductions have been sold by the museum since 1858. More recently, a for-profit subsidiary, V&A Enterprises (V&AE), was established to supplement the museum’s budget with income generated from commercial activities such as e-commerce and brand licensing. The V&A Picture Library joined V&AE in 2003 and became V&A Images.3

As V&AE’s then Managing Director, Jo Prosser, stated in 2011, “The unit should make money. If we stop making money, we should stop doing what we do.”4 Nowhere is the tension between generating profits and fostering collections access and scholarship more evident than in the museum picture library. The cost of creating, describing, and maintaining digital collections is high, yet the typical “customer” for museum collections is academic and non-commercial. Seeking to balance mission-focused and revenue-generating objectives, museum picture libraries have often looked to copyright to control their digitised collections.

Copyright and the public domain at the V&A

Like many other UK museums, the V&A claims copyright over digital reproductions of public domain works in its collections. Let’s look at an example from the V&A’s Explore the Collections website.

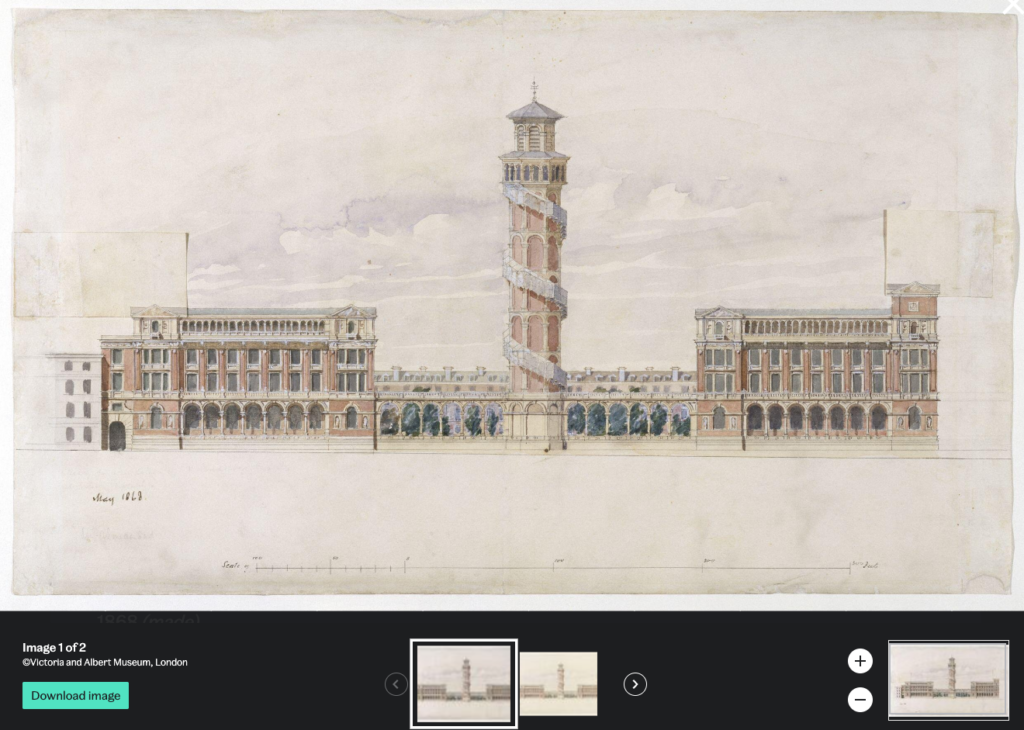

This pencil and watercolour drawing of proposed museum buildings is accompanied by the copyright notice: ‘© Victoria and Albert Museum, London’. It was created in 1868 after a sketch by Henry Cole, the first director of the South Kensington Museum (later known as the Victoria and Albert Museum). This copyright notice is attached to more than 450,000 images on the Explore the Collections website.

The website’s Terms and Conditions5 explicitly claim copyright over all content featured on V&A platforms:

‘… the intellectual property rights in all ‘Content’ (including images, editorial or descriptive text, footage or any other media) featured within the ‘Websites’ (www.vam.ac.uk, and all sub-domains) and selected social media platforms, is owned by the ‘V&A’ (the Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum) and other copyright owners as specified wherever possible.’

This approach is consistent with the V&A’s sister site, V&A Images, where Clause 10 of its Terms6 states:

‘The Client shall accompany any Reproduction of an Image with the credit line or copyright notice given in the form of “Victoria and Albert Museum, London” and, where appropriate, the author or authors’ name(s), unless otherwise agreed in writing by V&AE7. V&AE asserts the rights to a credit in accordance with sections 77 & 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.’8

Down the copyright rabbit hole

These broad copyright claims raise a key question: on what legal basis is the V&A asserting copyright in faithful digital reproductions of two-dimensional works that are themselves out of copyright? Why does the V&A interpret this aspect of copyright law differently from institutions like National Galleries Scotland, the Wellcome Collection, or York Museums Trust – none of which claim copyright in such reproductions?

Seeking clarity, I contacted the V&A’s Freedom of Information (FoI) Office. Here is a transcript of our email exchange, with minor edits to aid readability:

DM. Does the V&A claim copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright works in its collections?

V&A. The V&A claims copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright works in its collections where those images are original for the purposes of copyright law.

DM. On what basis in law are such claims made?

V&A. The legal basis on which the V&A justifies this position is information that only exists within legal advice to which a claim to legal professional privilege is maintained and which is therefore exempt from disclosure under s.42(1) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

DM. Has the V&A sought or received any legal advice on copyright in its digital images of out of copyright artworks in the last ten years, and in response to the THJ v Sheridan9 case?

V&A. We can confirm that within the last ten years, the V&A has sought and received legal advice on copyright in its digital images of out of copyright artworks, including in response to the THJ v Sheridan case.

DM. Will the museum release that advice?

V&A. The museum recognises that there is clear public interest in this subject and in the position that the V&A, as a publicly-funded body, adopts in relation to it. However the concept of legal professional privilege enables the museum to conduct frank and confidential discussions which include its legal advisers, which aid the museum in serving the public effectively.

Additionally, some of the relevant legal advice which it has received is both recent and live. The museum is not prepared to waive this privilege and believes that the exemption should be maintained.

DM. In the past five years, how much V&A image licensing income derived from works where the museum was the sole copyright holder? That is, income derived from image licensing contracts where no royalties were payable to third party rights-holders?

V&A. We do not keep records of which of our images qualify for copyright under copyright law and which do not. Therefore, we cannot answer your question. From a Freedom of Information perspective this means that the information that you have requested is not held by the museum.

DM. In your last message you stated that the V&A does not keep records of which of its images qualify for copyright under copyright law and which do not. In practice, I do not see how this can be the case. Please compare the following two items on the V&A Images website, noting the copyright statement for each image:

There is a clear distinction between the Dearle image, in which the V&A claims copyright, and the Cecil Beaton photograph, where Beaton’s estate is credited as a copyright holder. Copyright determinations appear to have been made by the V&A in each instance, and regarding other images on the V&A Images website. Please clarify your previous statements on this topic.

V&A. We think that the confusion stems from the fact that the V&A includes a copyright notice on all imagery but has not undertaken a copyright analysis on all images to establish whether or not the copyright in question is enforceable.

We could disclose how much image licensing income was derived from works where no royalties were paid to third parties, but it would not necessarily follow that this is income where the V&A was the sole copyright holder. We have very little content where we pay royalties to third parties, so almost all our picture library income would fall into this category.

[End of correspondence]

To summarise the key points:

Copyright claim: The V&A confirmed that it claims copyright in digital images of out-of-copyright 2D works in its collections ‘where those images are deemed original for the purposes of copyright law’.

Legal advice: The museum acknowledged that it had sought and received legal advice regarding its copyright policies, including in response to the THJ v Sheridan case. When asked about the legal basis for its copyright claims, the museum cited legal professional privilege and refused to disclose this information under Section 42(1) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

Income sources: The V&A disclosed details of its image licensing income over the last five years. However, it could not specify how much income was derived from images where the V&A was the sole copyright holder, as it does not maintain records on which of its images qualify for copyright under the law.

Copyright and the public interest

The public interest is ill-served when publicly funded museums assert broad copyright claims over their collections without disclosing the legal basis for these claims or verifying the subsistence of copyright before making such claims. The V&A is an important, high-profile custodian of cultural treasures. Its policy decisions matter to citizens and they influence its peers in the culture sector.

The common practice of museums asserting copyright over digital reproductions of public domain works impedes open access to and reuse of heritage collections. The V&A’s copyright practices – shared by several publicly funded national institutions in the UK – highlight the urgent need for broader reform in the museum sector. Unsupported copyright claims over public domain collections risk eroding public trust and positioning institutions as monopolists rather than stewards of cultural heritage.

As UK museums review their copyright policies in light of recent legal developments, there is hope for a shift toward more open and equitable access to cultural heritage. Such a shift would not only enhance public engagement but also support the academic and creative communities that rely on these resources. If leading institutions like the V&A do not reassess their approach, they risk undermining the very principles of openness and education that museums were founded to uphold and may also jeopardise their international relevance, as global peers increasingly adopt open access policies for their digitised collections.10

Footnotes

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/about-us ↩︎

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport (2024). https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/total-income-of-dcms-funded-cultural-organisations-20222023 ↩︎

- JISC Ithaka Case Studies in Sustainability (2009). V&A Images: Image Licensing at a Cultural Heritage Institution. https://sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/SCA_BMS_CaseStudy_V-AImages.pdf ↩︎

- JISC Ithaka Case Studies in Sustainability (2011). V&A Images: Scaling Back to Refocus on Revenue. https://sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/SCA_IthakaSR_CaseStudies_V-AImages_2011.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/va-websites-terms-conditions ↩︎

- https://www.vandaimages.com/terms.asp ↩︎

- In April 2011, after eight years of operation as a commercial unit within V&A Enterprises, V&A Images was disbanded and its functions were dispersed among V&AE and other museum departments. ↩︎

- Sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 cover the rights of attribution to copyrighted works; see https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents ↩︎

- THJ Systems Limited & Anor v Daniel Sheridan & Anor [2023] EWCA Civ 1354, https://caselaw.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ewca/civ/2023/1354 ↩︎

- Creative Commons, Douglas McCarthy and Andrea Wallace (2024). Moving Institutions Toward Open—Building on 6 Years of the Open GLAM Survey. https://creativecommons.org/2024/06/26/moving-institutions-toward-open-building-on-6-years-of-the-open-glam-survey/ ↩︎

© Douglas McCarthy, 2024. Unless indicated otherwise for specific images, this article is licensed for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Please note that this licence does not apply to any images. Those specific items may be re-used as indicated in the image rights statement within each slide. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt this article, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence, indicate if changes were made, and abide by the other licence terms.

The contents of this article are not legal advice and cannot be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice should be sought on a case-by-case basis.

Citation

McCarthy, D. (2024). Curiouser and curiouser: copyright and the public domain at the V&A. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13371149