An analysis of the inconsistencies in UK museums’ copyright claims over digital reproductions of public domain works

Introduction

In our online, globally connected era, cultural institutions are vital custodians of history and culture, preserving and making accessible millions of digitised artworks, manuscripts, and objects. Yet in the United Kingdom, a complex and inconsistent approach to copyright over digital reproductions of public domain works is creating barriers to access, let alone reuse. Some institutions claim copyright over their digital reproductions, while others do not, leaving potential users – such as researchers, educators, and creatives – facing a confusing landscape.

This article draws on newly acquired Freedom of Information (FoI) data from sixteen UK cultural institutions to explore their policies and practices around copyright. It highlights the stark disparities in interpretations of copyright law, examines the impact on access and reuse, and calls for a unified, transparent approach that reflects both the law and the public mandate of these institutions. This article argues that UK cultural institutions’ inconsistent approaches to copyright hinder public access to cultural heritage and it calls for a unified, transparent framework that aligns with established legal principles.

Background

In a series of articles this year, I’ve been examining how major UK cultural heritage institutions manage copyright and licensing for digital surrogates of public domain collections. After THJ v Sheridan analysed the implications of an important recent legal ruling on copyright and originality for British cultural institutions. Schrödinger’s copyright explored the paradox of different UK institutions claiming or disclaiming copyright over digital versions of the same works. Balancing access and income – the dilemma of museum image licensing discussed the tension between generating revenue and providing public access to digital collections, Curiouser and curiouser: copyright and the public domain at the V&A examined the V&A’s approach to copyright and digitised public domain works.

This article delves deeper into how UK cultural institutions assert copyright regarding digital reproductions of public domain works. It use FoI-sourced information from the following institutions: the British Library; the British Museum; the Government Art Collection (Department for Culture, Media and Sport); Imperial War Museums; the National Gallery; National Galleries Scotland; the National Library of Scotland; National Museums Scotland; the National Portrait Gallery; the Natural History Museum; Royal Museums Greenwich; the Science Museum Group; Tate; the Victoria and Albert Museum; and the Wallace Collection.

Methodology

The surveyed organisations represent a cross-section of the most significant holders of cultural heritage in the UK, collectively managing tens of millions of public domain works and receiving substantial public funding from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport1, and the Scottish Government2. Their policies directly influence how accessible these collections are to the public and the extent to which they can be reused for education, creativity, and innovation.

To gain clarity, I posed the following questions to each institution:

- Does your institution claim copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright visual works (such as prints or photographs) in its collections? If so, on what basis in law are such claims made?

- Has your institution sought or received any legal advice on copyright in its digital images of out of copyright artworks in the last ten years, and in response to the recent THJ v Sheridan case? If so, will you release that advice?

The purpose of asking these questions through the FoI process was threefold:

• To uncover information about copyright policies that institutions had either not made public or not communicated clearly.

• To gather information directly from the institutions themselves, ensuring it was provided in a timely and transparent manner, as required by FoI regulations.

• To understand the rationale behind the differing approaches to copyright that I had already observed.

The responses I received offer valuable insights into how cultural institutions, operating within the same legal framework, interpret copyright law and manage access to their digital collections of public domain works.

Findings from FoI responses

Do institutions claim copyright over digital reproductions?

The surveyed institutions provided varying responses to whether they claim copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright visual works, reflecting a striking inconsistency in interpretation and application of copyright law. Here are the responses given by each surveyed institution, and for comparison, a relevant excerpt from each institution’s online terms and conditions.

| Does your institution claim copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright visual works (such as prints or photographs) in its collections? If so, on what basis in law are such claims made? | |

| British Museum | Yes |

| FoI response: ‘Yes. The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘All the content on our website is protected by internationally recognised laws of copyright and intellectual property. The British Museum can decide under what terms to release the content for which we own the copyright.’3 | |

| Department of Culture, Media and Sport | No |

| FoI response: ‘The Government Art Collection does not assert copyright over 2D out-of-copyright images.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘Copyright of images: Images of works of art on this site are not covered by the Open Government Licence. If you wish to reproduce any of the works of art featured on this site, please contact the Government Art Collection, to supply you with an image of the work and grant the appropriate reproduction rights.’4 | |

| Imperial War Museums | No |

| FoI response: ‘IWM does not assert copyright in its surrogate images of Crown copyright expired works, but we continue to supply high resolution copies of these under licence. Museums can charge for the use of images, and do so under multiple legal frameworks, whether that be Charity law, pre-Brexit EU legislations or current UK legislation governing National collections. The framework for that is laid down in Re-use of Public Sector Information (PSI) Regulations and our contract terms. The direct and indirect costs of producing an asset can be recouped through licensing or service fees regardless of its copyright status. IWM is not claiming copyright in the linked image.’5 Website Terms and Conditions: ‘IWM’s websites are copyright of Imperial War Museums (© IWM), whilst the copyright in the material which is hosted on IWM’s websites belongs to IWM as well as other third parties.’ | |

| National Galleries Scotland | No |

| FoI response: ‘NGS does not claim copyright on digital images of artworks that are out of copyright. All images on our website of works that are out of copyright have the caption Creative Commons CC by NC and no additional copyright line.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘‘Images of works where copyright has expired or where a copyright holder has agreed to release the image are available for you to use under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 3.0 Licence.’6 | |

| National Gallery | Declined to say |

| FoI response: ‘This is not a question for FOIA; this is asking the Gallery to give an opinion on a position rather than seeking information the Gallery holds.’ (See below for discussion of this reply.) Website Terms and Conditions: ‘All copyright, trade marks, design rights, patents and other intellectual property rights contained in the Website and all content available on the Website shall remain the property of the National Gallery or its licensors. All such rights are reserved.’7 | |

| National Library of Scotland | No |

| FoI response: ‘The Library does not claim copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright works in our collections anymore. The Library recognises that there is no legal basis for claiming fresh copyright in digitisations. This means we do not try to enforce control over the re-use of out of copyright materials.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘Works that are not in copyright: Public Domain Mark – This statement means the work is not protected by copyright. You may re-use the work as you please, without further permission, including for commercial purposes. No Copyright – Contractual Restrictions – This statement means the work is not protected by copyright, but there are contractual restrictions that limit how you may re-use it.’8 | |

| National Museums Scotland | Yes |

| FoI response: ‘Yes, National Museums Scotland claims copyright of the digital image of 2D out-of-copyright works. The approach used by National Museums Scotland is based on our interpretation of copyright law. Since the ruling was made we have taken advice from a recognised expert in our sector9, and undertaken peer consultation with other leading museums and galleries.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘All images and other content on nms.ac.uk are copyright National Museums Scotland, unless otherwise stated. Where images and other content have copyright belonging to other individuals or organisations, this is clearly stated on our website.’10 | |

| National Portrait Gallery | Yes |

| FoI response: ‘We are not aware of any legislation nor case law in the UK to date, that clearly states that any images of works in the National Portrait Gallery would not qualify for copyright protection. UK legislation on copyright is governed by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The Gallery has also taken on board BAPLA’s [British Association of Picture Libraries and Agencies] clarification regarding the interpretation of new case law, most specifically THJ vs Sheridan, which asserts that the case simply highlights the complex question of what qualifies as ‘original’ under copyright law.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘The National Portrait Gallery owns, generates and makes use of a range of items protected by IPR legislation. You may access, download and/or print contents for non-commercial research and private study purposes.’11 | |

| Natural History Museum | No |

| FoI response: ‘The Natural History Museum does not claim copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright works in its collections. The example you have highlighted of copyright assertion in items from the Endeavour voyage is from our legacy webpages, the collections on which were first published on our website before this decision was taken and carry out of date metadata. Unfortunately, some similarly affected content remains online with legacy copyright information. We intend to update this.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘Intellectual Property: The NHM or its licensors or contributors own the copyright and all other intellectual property rights in the Marks and Information on the Website.’12 | |

| Royal Museums Greenwich | Yes |

| FoI response: ‘Under UK copyright law, (CDPA 1989), the museum claims copyright in the digital assets created by our professional photographic studio. This process requires skill, knowledge, judgement, creativity and labour, significant time and expertise which are needed to create an original digital asset. We are not producing slavish copies but creating new original artistic works by investing intellectual creativity in the act of production of the asset.’ (See below for analysis of this reply.) Website Terms and Conditions: ‘All images and information provided by RMG Images or downloaded from the website are the property and/or copyright of NMM (unless stated otherwise). The moral rights of NMM and its authors of works represented on this site have been asserted.’13 | |

| Science Museum Group | No |

| FoI response: ‘SMG is not actively asserting copyright where applicable (such as in the case of the examples provided). Captions for these images [on the SMG website] are legacy data. Our statement on intellectual property is published on our website: Website Terms and Conditions: ‘All copyright, trade marks, design rights, patents and other intellectual property rights (registered or unregistered) in and on the Websites are owned by the Science Museum Group or are included with the permission of the owner of the rights as specified wherever possible.’14 | |

| Tate | No |

| FoI response: ‘Tate’s position is that it does not claim copyright, as defined under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, in its digital images which solely portray 2D out-of-copyright works in its collection.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘All copyright, trade marks, design rights, patents and other intellectual property rights (registered and unregistered) in and on tate.org.uk and all content (including all applications) located on the site shall remain vested in Tate or its licensors (which includes other users). You may not copy, reproduce, republish, disassemble, decompile, reverse engineer, download, post, broadcast, transmit, make available to the public, or otherwise use tate.org.uk content in any way except for your own personal, non-commercial use. In certain prescribed circumstances, you may adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any tate.org.uk content for your own personal, non-commercial use, with the prior written permission of Tate which will be indicated against the relevant tate.org.uk content.’15 | |

| Victoria and Albert Museum | Yes |

| FoI response: ’The V&A claims copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright works in its collections where those images are original for the purposes of copyright law.’ Website Terms and Conditions: ‘Please note that the intellectual property rights in all ‘Content’ (including images, editorial or descriptive text, footage or any other media) featured within the ‘Websites’ (www.vam.ac.uk, and all sub-domains) and selected social media platforms, is owned by the ‘V&A’ (the Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum) and other copyright owners as specified wherever possible.’16 | |

| British Library | Unable to respond in time |

| FoI response: n/a Website Terms and Conditions: ‘The audio, video, text, images, or other material made available on the Website by the Library are either protected by the copyright of third parties, are the copyright of the British Library Board, or are materials which are in the public domain or made available under a Creative Commons licence. Where content is marked as public domain, the Library believes it to be in the public domain in most territories and is unaware of any current copyright restrictions on the content either because the term of copyright has expired in most countries, or because after reasonable efforts no evidence has been found that copyright restrictions apply. You are free to use this material as you wish, but please note that the Library does not warrant that use of the content will not infringe on the rights of third parties.’17 | |

| Wallace Collection | Did not respond |

| FoI response: n/a Website Terms and Conditions: ‘Copyrighted material on this website is available for non-commercial and educational purposes under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 (Unported) licence. The following acts are not permitted in respect of any of the content featured on the Wallace Collection’s website: Reproduction of website content for commercial purposes, or any rental, leasing or lending of content obtained or derived from the website.’18 | |

The responses highlight significant inconsistencies in how UK cultural institutions interpret and apply copyright law, even though they operate within the same legal framework. Organisations are managing straightforward digital images of public domain works in entirely different ways: some assert copyright over their digital reproductions, others releasing them openly, accepting their public domain status. Among institutions that claim copyright, the justifications provided were equally varied, with some citing legal statutes and others invoking outdated principles such as the “skill, labour, and judgement” argument.

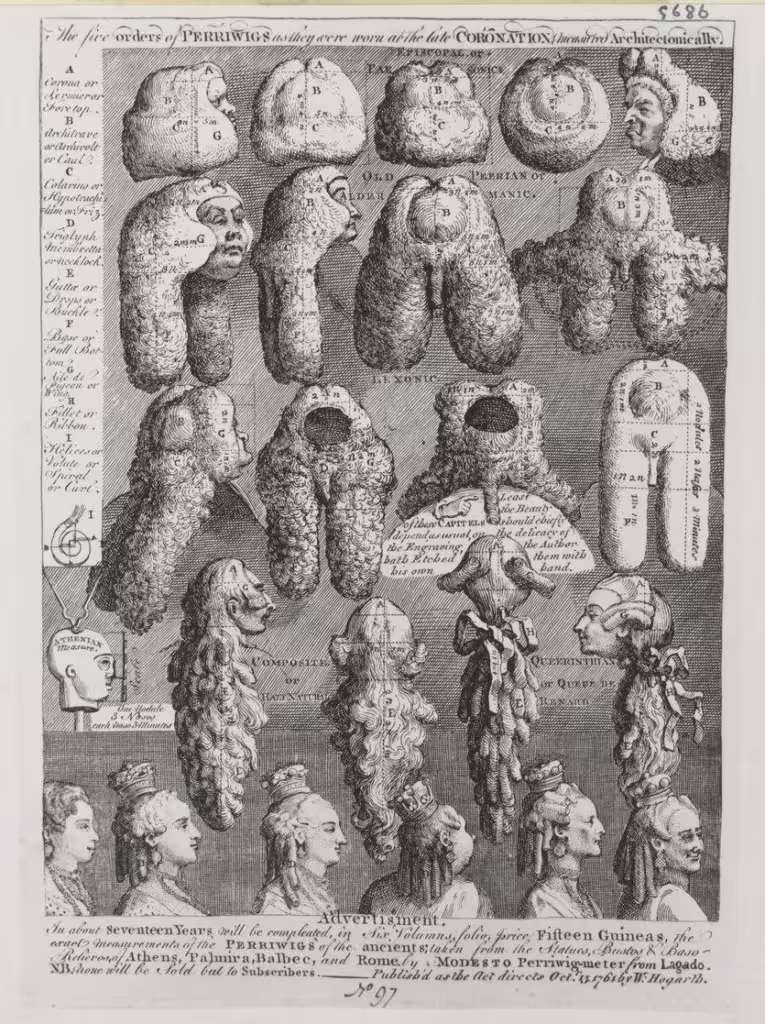

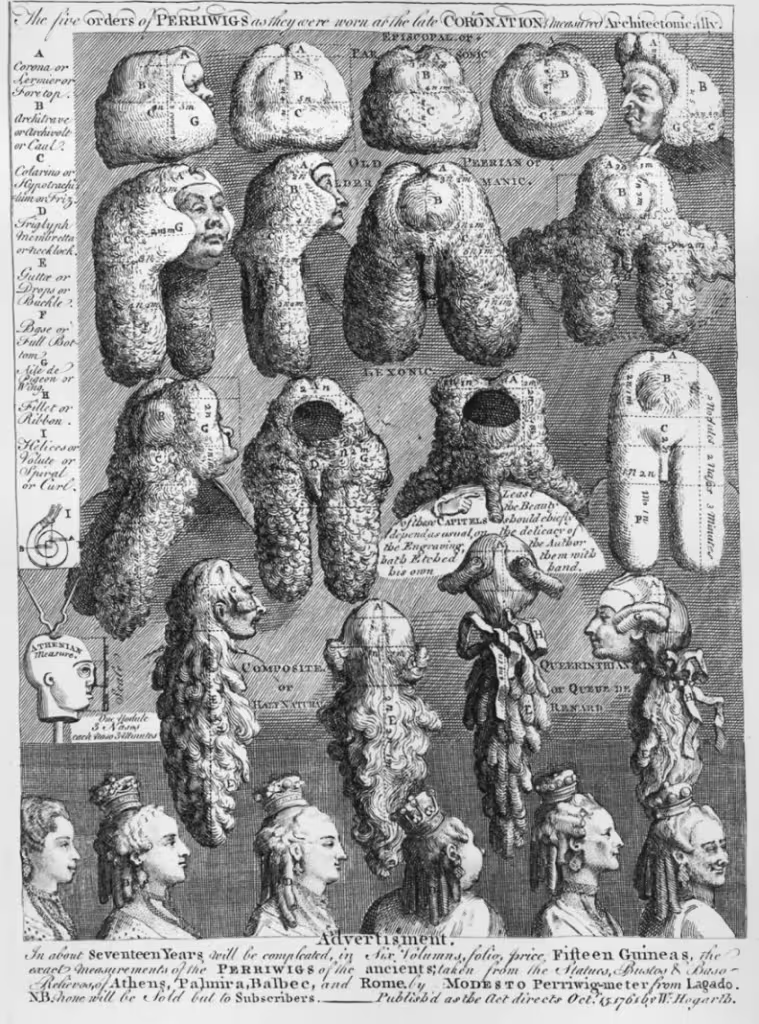

To see what this looks like in practice, let’s compare two images of William Hogarth’s Five Orders of Perriwigs, 1761. The Victoria and Albert Museum claims copyright in its digital surrogate (left) whilst the Government Art Collection does not claim copyright in its image (right).

UK copyright law: originality and public domain works

In 2014, the UK Intellectual Property Office issued guidance regarding digital images and the threshold of originality required for copyright to subsist under UK law:

‘Copyright can only subsist in subject matter that involves the author’s own “intellectual creation.” A straightforward copy of a public domain work does not meet this standard, as it lacks the originality required for copyright protection.’19

The divergent practices of the surveyed organisations partly reflect their own interpretations of what qualifies as an “original” work under UK law. Some institutions follow the IPO’s guidance in accepting that a new copyright does not arise in faithful, unoriginal reproductions of public domain works. Others, like Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG), invoke the outdated ‘sufficient skill, labour, or effort’ argument to justify copyright claims – let’s examine that argument in a little more detail.

Case in point: Royal Museums Greenwich

When I asked why Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) claims copyright over digital surrogates of public domain works, the following explanation was given:

“Royal Museums Greenwich invests a significant amount of time and resource digitising its valuable collections to make them available to the public and provide access for all. Under UK copyright law, (CDPA 1989), the museum claims copyright in the digital assets created by our professional photographic studio. This process requires skill, knowledge, judgement, creativity and labour, significant time and expertise which are needed to create an original digital asset. We are not producing slavish copies but creating new original artistic works by investing intellectual creativity in the act of production of the asset.”

RMG’S citation of the CDPA act – not a specific provision or reference to originality – is also vague. Their reasoning misinterprets modern UK copyright law requirements around originality. Although historically, English copyright law had a low bar for originality, defined by ‘sufficient skill, labour, or effort’, this has changed in recent decades, under the influence of European Union (EU) law, such as Article 6 of the EU’s 2006 Copyright Term Directive20 (which set the threshold of originality for copyright in photographs) and jurisprudence from The Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU).

The key principle is that a work is eligible for copyright protection only if it results from ‘creative freedom’ and ‘free and creative choices,’ ultimately reflecting the author’s ‘personal touch.’ Can the reader identify any of these qualities in Royal Museums Greenwich’s digital reproduction of a James Gillray print?

Impact of copyright assertions

The surveyed institutions that assert copyright over straightforward digital reproductions of public domain works are disregarding the guidance of the UK IPO and the Court of Appeal’s latest decision, instead erecting barriers around works that should be freely accessible and reusable. Potential users of these collections face a confusing and fragmented landscape, where access rights vary not by the nature of the work but by the institution holding it. This lack of uniformity impacts researchers, educators, and creators, who must navigate each institution’s unique copyright stance and terms of use to understand their rights to use digital reproductions. Educators wishing to incorporate digitised artworks into teaching materials may face legal uncertainties, while researchers are discouraged by inconsistent policies when seeking to analyse or republish these works. Such inconsistency risks undermining public confidence in the institutions as stewards of accessible cultural heritage, often held in trust for the public. Moreover, it creates potential legal ambiguities that could complicate the reuse of these works, particularly as more collections become available online.

Ultimately, this disparity highlights a need for clearer, unified guidelines on copyright misuse within the cultural sector. Standardised practices that align with IPO guidance and established case law would not only benefit users but would also reinforce these institutions’ shared role as custodians of cultural heritage, fostering openness and accessibility across the sector.

Outlier: the National Gallery

Only one surveyed organisation declined to say whether it claims copyright in its digital images of 2D out-of-copyright collections: the National Gallery. This was the justification provided:

“This is not a question for FOIA; this is asking the Gallery to give an opinion on a position rather than seeking information the Gallery holds. We can confirm, however, that following reasonable searches of the relevant business area, no recorded information is held… no recorded information exists which confirms the Gallery’s policy on whether it claims copyright in digital images of 2D out-of-copyright works beyond the information you referenced (information contained on the Gallery’s website).”

It is surprising to say the least that the National Gallery asserts that it holds no recorded information on such an important aspect of its copyright policy, given how important copyright management is to collections management. This claim appears inconsistent with the unambiguous assertions made on its website, where the Terms of Use21 state:

“All copyright, trademarks, design rights, patents and other intellectual property rights contained in the Website and all content available on the Website shall remain the property of the National Gallery or its licensors. All such rights are reserved.”

Furthermore, the Terms and Conditions of the Gallery’s dedicated picture library website22 are equally explicit on this point:

“NGG [National Gallery Global Limited] represents, warrants and undertakes for the Duration that: either it or the Board of Trustees of the National Gallery owns the copyright in the Image; it is fully entitled to grant Licensee the rights described herein.”

The National Gallery’s statement that ‘no recorded information exists’ to support these copyright assertions raises significant questions about how the Gallery manages and records its copyright policy, especially given the definitive language used in its publicly available terms.

Now let’s review the responses given to the second question, ‘Has your institution sought or received any legal advice on copyright in its digital images of out of copyright artworks in the last ten years, and in response to the recent THJ v Sheridan case? If so, will you release that advice?’.

Legal advice on copyright policies

Four institutions acknowledged seeking legal advice on their copyright policies – British Museum, National Gallery, Tate, Victoria and Albert Museum – but all declined to disclose the details of that advice, citing section 42 of the UK Freedom of Information Act23, which exempts information protected by legal professional privilege.

This exemption is intended to enable organisations to withhold legal counsel if deemed necessary, a right that can be justified to ensure private consultations on sensitive topics. However, invoking section 42 for policy-related advice can also hinder public understanding and create perceptions of secrecy. Given that these institutions are publicly funded, such refusals to disclose may feel, to some, like an obstruction of transparency. This is particularly relevant when legal advice directly affects public access to public domain collections.

Transparency is essential in fostering public trust, yet by withholding policy-related legal advice around copyright and their digital collections, the British Museum, National Gallery, Tate, and Victoria and Albert Museum are creating barriers to understanding their rationale and undermining public trust in the use of copyright itself. Recalling that they are public bodies funded by British taxpayers, the decision to withhold information may seem contradictory to their mission of public service, which risks eroding public confidence.

Case in point: Victoria and Albert Museum

When I requested the legal basis for its copyright claims over digital images of 2D public domain works, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) initially answered part of my enquiry but withheld its legal justification under section 42(1) of the FOIA, citing legal privilege. In my request for an internal review, I argued that significant public interest warranted transparency in this case.

In its review, the V&A acknowledged the public interest but concluded that the public interest in maintaining legal professional privilege outweighed the need for transparency. The museum justified its stance by citing guidance from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and Tribunal decisions, which underscore the importance of safeguarding open communication between clients and legal advisers. The V&A also indicated that the withheld information likely falls under both “advice” and “litigation” privilege, as copyright policy is a “contentious issue” with potential for future litigation. Despite recognising some public interest in the matter, the V&A maintained its refusal, reinforcing its position that legal privilege is paramount.

The V&A’s response also contained a noteworthy statement thatI have highlighted here in bold text:

‘The subject matter of Mr McCarthy’s original information request related to the V&A’s policies concerning copyright in photographs of out-of-copyright works. This is a contentious issue, and I am aware that a small number of influential and well-funded commentators have publicly criticised the policies on this subject adopted by the V&A and other national museums… I accept that there is clear interest in this subject from certain individuals but I have seen no evidence that this subject is of concern to a wide sector of the public.’

This directly expressed opinion (unaccompanied by any evidence to substantiate it) seems to step beyond the bounds of what one would expect from Freedom of Information correspondence on a point of law and policy. The response hints at a defensiveness around this subject, and a disconnect from the frequent public debates on this topic, that may hinder open discussion of policy.

Conclusion

The responses of the surveyed cultural institutions outlined in this article reveal a patchwork of inconsistent approaches to copyright as it pertains to digital surrogates of public domain collections. Five of the surveyed organisations claim copyright in such works, seven claim they do not. Of those seven, only two were confirmed as having website policies that accept and state the public domain status of such images. All operate under the same legal framework and all are funded by either the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, or the Scottish Government.

For institutions entrusted with public heritage and supported by public funds, this confusing and fragmented approach restricts access to important public collections. A unified and transparent approach to copyright would benefit not only the institutions themselves but also their audiences, especially potential reusers of digital collections who wish to incorporate them in educational, creative and commercial projects.

A good starting point would be aligning with the guidance of the Intellectual Property Office, and embracing transparency around policy positions. A collaborative effort among UK cultural institutions to develop consistent copyright policies would ensure clarity around access and reuse for all users. These steps would help to ensure that digital images of public domain works become fully accessible and reusable, in accordance with the prevailing law and the institutions’ public mandate. By embracing this opportunity for reform, UK cultural organisations can reaffirm their role as sources of accessible heritage in the digital age.

Footnotes

- https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/dcms-sponsored-museums-and-galleries-annual-performance-indicators-202223 ↩︎

- https://www.gov.scot/policies/arts-culture-heritage/annual-culture-funding/ ↩︎

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/terms-use/copyright-and-permissions ↩︎

- https://artcollection.dcms.gov.uk/crown-copyright/ ↩︎

- https://www.iwm.org.uk/corporate/policies/copyright ↩︎

- https://www.nationalgalleries.org/copyright-image-licensing ↩︎

- https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/terms-of-use ↩︎

- https://www.nls.uk/copyright/ ↩︎

- Further correspondence revealed that this advice was given verbally to NMS staff members during a training event on a different topic, therefore it is not “recorded” information in FoI terms. ↩︎

- https://www.nms.ac.uk/website-terms-of-use/ ↩︎

- https://www.npg.org.uk/business/images#acc73 ↩︎

- https://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/website-terms-conditions.html ↩︎

- https://images.rmg.co.uk/terms-and-conditions/ ↩︎

- https://www.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/terms-and-conditions/ ↩︎

- https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/policies-and-procedures/website-terms-use ↩︎

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/va-websites-terms-conditions ↩︎

- https://www.bl.uk/terms/ ↩︎

- https://www.wallacecollection.org/copyright-and-images/ ↩︎

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/copyright-notice-digital-images-photographs-and-the-internet/copyright-notice-digital-images-photographs-and-the-internet ↩︎

- ‘Article 6: Protection of photographs. Photographs which are original in the sense that they are the author’s own intellectual creation shall be protected in accordance with Article 1. No other criteria shall be applied to determine their eligibility for protection. Member States may provide for the protection of other photographs.’

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32006L0116 ↩︎ - https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/terms-of-use ↩︎

- https://www.nationalgalleryimages.co.uk/terms-and-conditions/ ↩︎

- https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/foi/freedom-of-information-and-environmental-information-regulations/section-42-legal-professional-privilege/ ↩︎

© Douglas McCarthy, 2024. Unless indicated otherwise for specific images, this article is licensed for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. Please note that this licence does not apply to any images. Those specific items may be re-used as indicated in the image rights statement within each slide. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt this article, as long as you give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licence, indicate if changes were made, and abide by the other licence terms.

The contents of this article are not legal advice and cannot be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice should be sought on a case-by-case basis.

Citation

McCarthy, D. (2024). Anarchy in the UK. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14192608