Fredrik Emdén from the Swedish National Heritage Board recently interviewed me about museums and NFTs. This is an English translation of the original article published in Swedish on the Riksantikvarieämbetet website.

NFT stands for the English term “Non-Fungible Token”. Non-fungible is used as a term to describe an object that is unique, something that cannot be replaced by another object. When we talk about an NFT in the art world, we mean a digital work of art, for example a newly created video artwork or digital collector’s object, which is provided with metadata and stamped with a cryptographic code. This creates a so-called block chain that guarantees the object’s authenticity, creator and owner. Since the artist Mike Winkelmann, better known as Beeple, sold an NFT for $69.4 million in March last year, interest in this concept has skyrocketed.

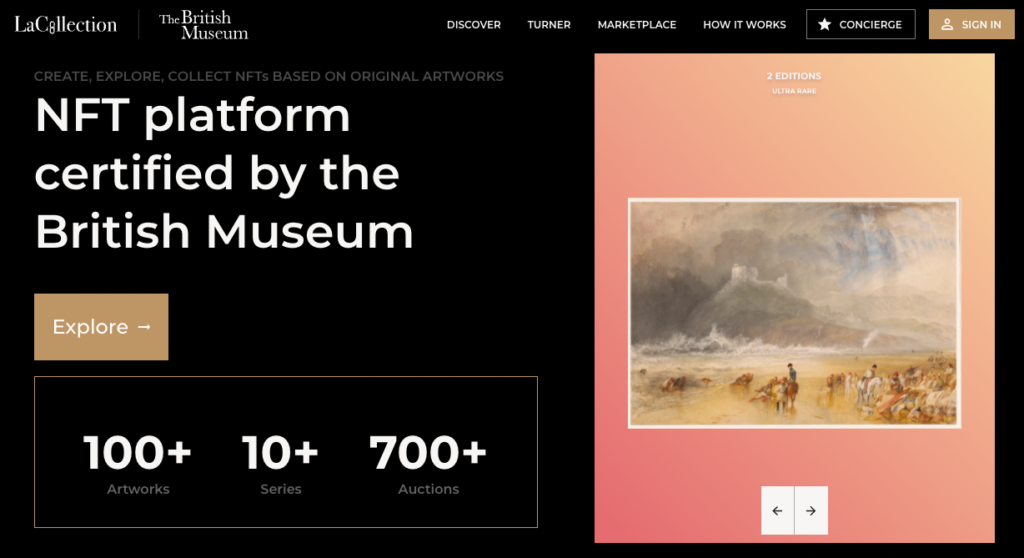

In the autumn of 2021, the French company LaCollection launched an NFT platform in collaboration with the British Museum. Around the same time, the open access researcher and author, Douglas McCarthy, editor of the publication Open GLAM and Collections Engagement Manager at Europeana, wrote an opinion piece for Apollo magazine. Responding to the question, ‘Should museums be dabbling in NFTs?’ Douglas and Bernadine Bröcker Wieder, CEO of Vastari, each shared their own perspectives in the magazine.

Douglas’s essay mentions the British Museum’s entrance into the NFT market by auctioning NFTs of more than 200 works by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, including Under the Wave off Kanagawa, 1830–33, one of the world’s most reproduced images (and one which McCarthy has written about previously). The notion of creating artificial scarcity with such a public domain work – freely available and infinitely reproducible – for commercial purposes, struck McCarthy as rather curious.

- “‘The Great Wave’ is one of the world’s most famous artworks. Anyone can freely download a high-resolution image from the Library of Congress and from the websites of several other institutions. So for anyone – let alone a museum – to market “limited” editions” of such freely available, out of copyright works like the Hokusai prints seems more than a little odd.”

World famous institutions entering the NFT marketplace, like the Uffizi Gallery, the Hermitage and the British Museum, are able to trade off the global strength of their brands, he says to Omvärld och insikt. (Needless to say, this dynamic is less applicable to smaller, less famous cultural institutions.)

Retaining copyright control

McCarthy is not surprised that the first interactions between the museum world and NFT actors (such as La Collection) have – so far – almost always involved museums without open access policies.

- “The first museums that began selling NFTs all had something in common: a track record of claiming copyright over simple reproductions of public domain works, and using these copyright claims to assert control and monopolize revenue generation opportunities – typically, supplying and licensing images for reproduction in books, TV programmes and other media – from digital versions of their collections. So, one could see the NFT ventures of these museums as simply the status quo of monetisation and control being transposed into a new context”, he says.

Last month, the Belvedere in Vienna announced its intention to auction 10,000 NFTs based on Klimt’s famous painting The Kiss on Valentine’s Day. “Belvedere naturally strives to be one of the most prestigious cultural institutions in the digital world and thereby reach a new audience,” was CEO Stella Rollig’s motivation for why the Vienna Museum a few weeks ago chose to package Kyssen digitally and sell it as NFTs. The Belvedere became the first institution with an open access (or “Open GLAM”) collections policy to market NFTs, Douglas noted.

Is it reasonable for museums to embrace open access and sell NFTs?, he wonders.

- “Many people might suggest a fundamental conflict of interest here, because cultural heritage institutions, especially those that are publicly funded, exist to promote education and the sharing of knowledge for social benefit. Sharing their collections is an essential tool in doing this. So it is not surprising if people feel cynical about museums that use copyright to control and monetise public collections – and now sell NFTs of these works.”

“It is important that we as a museum constantly adapt to new markets and find new ways to reach people we may not reach through traditional channels,” commented Craig Bendle, licensing officer at the British Museum, the museum’s investment in NFT this autumn.

Douglas is not convinced by these explanations.

- “I find this kind of messaging a little hard to believe. It’s been proven that the most effective way for museums to increase the reach of their collections is to adopt open access policies and share their digital collections as widely as possible on this basis.”

Tread carefully

With regular instances of major fraud and plagiarism in the NFT space, and the heavy environmental impact of the blockchain technologies upon which NFTs currently rely, public skepticism about NFTs is widespread. Therefore, museums thinking about getting involved in NFTs should tread very carefully, McCarthy says.

- “It takes years to build public trust in your brand – and a moment to damage it. Cultural institutions are long term operations with important public missions; associating themselves with volatile marketplaces like NFTs, based on the financialisation of public collections, carries significant risk.”, McCarthy says.

- “My sense is that most people working in the cultural heritage sector understand the importance of a longer perspective for their work. Museums aren’t startups looking for VC investment or having an IPO on the horizon”, he continues.

He acknowledges that for some contemporary artists, NFTs appear to be an opportunity to make money from their work in ways which they lack today. Beeple is perhaps the most brilliant example.

- “Those who are positive about it probably come from the creative side, “in this way I can finally make money on my art, where the traditional art world does not succeed”. The idea that it can be possible to make money on future sales, that every time an NFT is sold, money can go back to the artist, the possibility of tracking and revenue streams, is certainly appealing. However, there is currently a great deal of uncertainty in the NFT sector, as evolving technologies, smart contracts and competing platforms fight for supremacy. Indeed, the web3 promise of decentralization seems to be undermined by the growing domination of platforms like OpenSea. At the present time, ‘platform is law’ seems truer than ‘code is law'”.

A few days after the interview, McCarthy’s misgivings were confirmed when OpenSea users were subjected to a phishing operation and were scammed out of $1.7 million worth of NFTs.

- “Follow web3 is going great on Twitter and you’ll see symptoms of a chaotic, immature and insecure ecosystem every day. It may well be that, as in many other areas of life, we’ll end up in an oligopoly with a few large players dominating the global NFT market.”

Would Douglas consider going to Seattle to visit the new NFT Museum opening there?

- “Sure, if someone buys me a first-class ticket! If nothing else, one can say with confidence that this period will provide rich material for historians, social scientists and economists. This story is not over yet – let’s see where it goes next.”