When the British Museum recently announced its intention to sell NFTs of Hokusai prints, many seemed surprised, intrigued or somewhat bemused. ‘Museum Twitter’ lit up with passionate threads, heated discussion and sarcastic memes. The British Museum, however, is not the only venerable institution to enter this voguish domain. This year the State Hermitage Museum, the Uffizi Galleries and the Whitworth Art Gallery have also sold NFTs based on their collections.

In May, after the Uffizi sold an NFT of Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo for $170,000 in May, its director Eike Schmidt said, ‘It’s not a change of direction in terms of revenue, it is an additional revenue’. In July, The Hermitage reportedly earned $440,500 from auctioning NFTs of five masterpieces by Giorgione, Leonardo da Vinci, Kandinsky, Monet and Van Gogh. The museum’s director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, said that the auction was ‘an important stage in the development of the relationship between person and money, person and thing.’

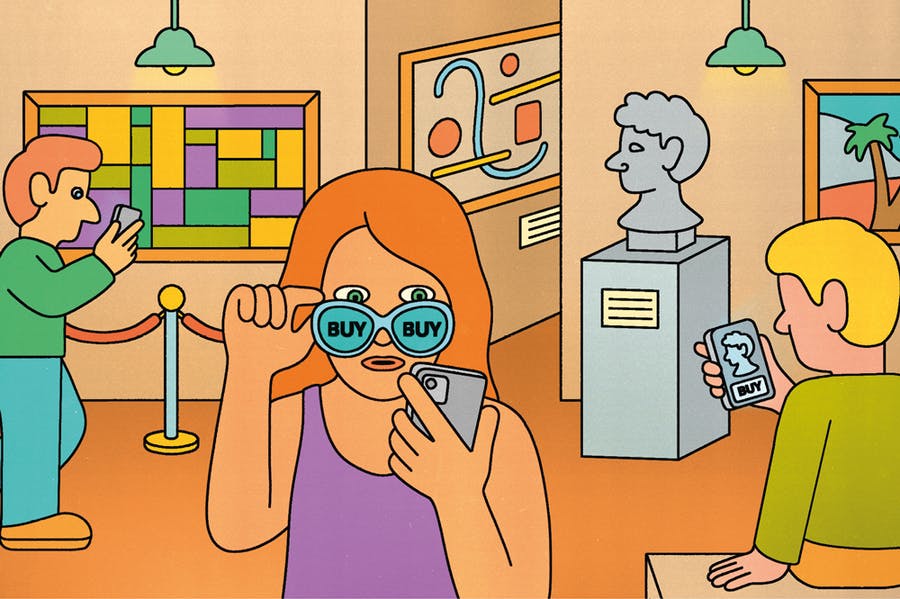

At first glance these ventures seem to encapsulate the ethical tension between museums, on the one hand, democratising access to their collections and, on the other, financialising them as assets in NFT marketplaces. Take a moment to reflect, however, and you might conclude that they are entirely in keeping with normal museum practice. To understand why, we need to make a brief detour into the world of copyright.

Like many museums in the UK and around the world, the British Museum, to take just one example, uses copyright to restrict reuse of its digital collections. It claims new copyrights when it makes digital facsimiles of public domain works in its collections – works in which copyright no longer exists, or never existed in the first place – just like the Hokusai prints from which the museum is now minting NFTs. Do these digital facsimiles actually qualify for copyright protection? The relevant law is complex and lacks international harmonisation. The legitimacy of this copyright claim is questionable and hotly debated.

Claiming copyright in these digital surrogates allows museums to erect a legal scaffold upon which restrictive reuse policies can be built. It enables their attempts (however vain they may be in practice) to monopolise the supply, publication and monetisation of digital collections. Image supply and reproduction fees can be ruinously expensive and the negative effects of such restrictive policies on authors and academics – especially those working in image-focused research fields such as art history – are well known.

According to the website of LaCollection, the British Museum’s commercial partner, ‘Each NFT is associated with a certificate of authenticity, signed by the art institution that owns the original artwork’. This statement will raise the eyebrows of many art historians. ‘The Great Wave’ was the first print from Hokusai’s series ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’ (Fugaku sanjûrokkei), of which around five thousand impressions were printed. It has since become of the most reproduced and well known images in the world. So the notion of buying a ‘super rare’ editioned token of the Hokusai print is rather odd.

To market limited edition NFTs of public domain works is to confect scarcity where none exists. Prints of ‘The Great Wave’ are held in museum collections all around the world and several of these institutions offer high-resolution digital files of ‘The Great Wave’ freely available for download and unrestricted reuse by anyone, anywhere – no strings attached.

The massive energy consumption of Proof of Work (Pow) blockchains, currently used as the basis for cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, upon which NFTs are based, deepens the ethical conundrum for museums, running counter, as it does, to their stated intention of reducing their carbon footprint.

In 19th century Japan, the right to manufacture and disseminate printed works was called zôhan (possession of blocks). Museums selling NFTs of their collections today have unconsciously revived zôhan on 21st-century blockchains. The price of a Hokusai print in 1842 was fixed at 16 mon, approximately the cost of two portions of noodles. At the time of writing, bidding on the British Museum’s first NFT of ‘The Great Wave’ has surpassed £6,000. If Hokusai were alive today, he would surely be astonished.

This article was commissioned by and originally published in the November 2021 issue of Apollo magazine.