State Library and Archives of Florida, Public Domain Mark

In spring 2018Andrea Wallace and I embarked upon a mission to discover how many cultural heritage institutions make their digital collections available for free reuse, and how they do this. My third post on theOpen GLAM Survey discusses Open Access Scope and argues that this facet is essential to a true understanding of the open access landscape.

Instances of open access

As I described in a previous post, the Open GLAM Survey records instancesof open access in the global cultural heritage sector. These instances are often singular occurrences and the reader should not equate them with blanket open access policies.

As one would expect from a Survey that spans small regional archives to national museums, the volume of data released openly by the surveyed institutions varies enormously: from a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of digital objects. So does the scope of open access: the proportion of a GLAM’s collections eligible for open access publication that it actually releases on open access terms.

To bring these nuances into focus, let’s analyse and compare two surveyed institutions that represent very different approaches in terms of the scope and scale of their open access practice.

1. Museums Victoria

Museums Victoria Collections is the collections portal of Australia’s Museums Victoria. It provides access to more than one million records relating to the natural sciences and humanities. Museums Victoria has adopted the Creative Commons legal tools and its collections website allows users to browse and filter their search results by ‘Image Licence’.

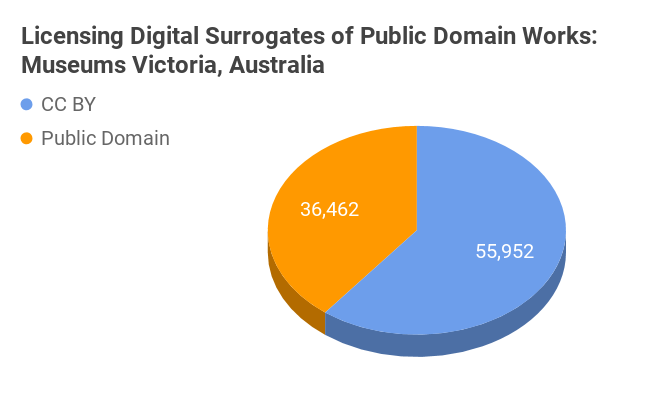

This filter function means we can see which legal tools Museums Victoria uses to label its digitised collections. If we narrow our search results to only show open access images, it becomes clear that Museums Victoria predominantly uses the Public Domain Mark and the CC BY licence:

In terms of its licensing rationale, Museums Victoria appears to deploy the Public Domain Mark for 2D images of its out-of-copyright works (example) and the CC BY licence for its photographs of 3D collections objects (example) and items where other legal restrictions exist.

Overall, we can state with confidence that Museums Victoria publishes its digitised collections on open access terms whenever possible.

2. Victoria and Albert Museum

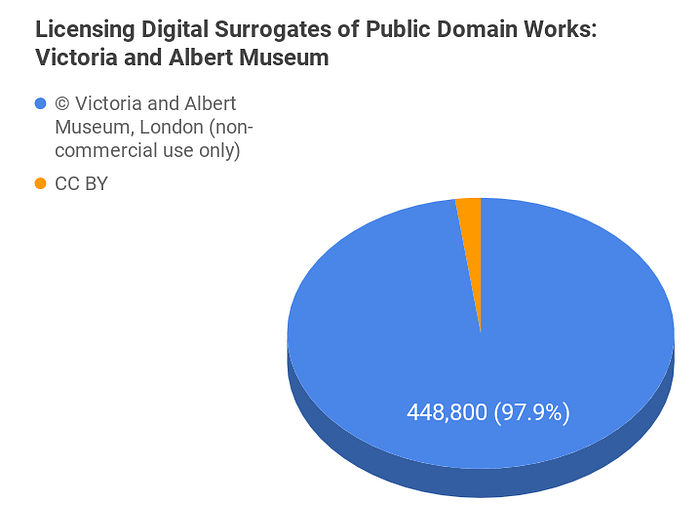

The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Search the Collections site gives access to 783,605 images of its collections. Search the Collections does not use Creative Commons legal tools and, as with many museums’ collections websites, it is not possible to search or filter results to show images of objects which the museum believes to be out of copyright. However, by using the date filter to just show objects made before 1900, we can reach an approximation of items likely to be in the public domain.

Search the Collections’s terms assert that the Board of Trustees of the Victoria & Albert Museum’s owns the copyright of all online ‘Content’, including images, editorial or descriptive text, or other media (respecting the rights of other copyright owners, of course).

Downloading images free of charge for non-commercial use is permitted for images of objects that the V&A deems to be out of copyright. The relevant process involves users ticking a series of boxes and acknowledging the museum’s terms and conditions, as shown below:

Given its copyright policy, one might wonder why the V&A is listed in the Open GLAM Survey. The V&A’s inclusion is due to its release of 10,000 images with a CC BY licence on Europeana, as part of its involvement in the Europeana Fashion project. The chart below puts this instance in the wider context of the V&A’s licensing practice:

Open Access Scope in the Open GLAM Survey

As these contrasting examples demonstrate, the manner and scope of open access policy and practice vary greatly across the institutions in the Open GLAM Survey. Museums which make some of their eligible data available for free reuse typically do so when involved in a specific project or event. Beyond the remit of such projects, GLAMs may maintain restrictive policies for the majority of their digital collections.

Attempting to highlight these disparities in the Survey, we introduced ‘Open Access Scope’ (in spreadsheet column F) to indicate whether we believe that a GLAM has released someor allof its eligible data on open access terms. (For the purposes of the Survey, ‘eligible data’ means digital surrogates of museum-held objects in the public domain where any term of copyright for the material object has expired or never existed in the first place.)

Accordingly, for the two above examples, the Open Access Scope of Museums Victoria is listed as ‘all eligible data’ and the Open Access Scope of the V&A is listed as ‘some eligible data’.

An important caveat is that it’s difficult to discern this information because GLAMs rarely communicate it: institutions that are explicit about their open access policies, such as Sweden’s Nationalmuseumor The Cleveland Museum of Art, are the exceptions. Whenever Andrea and I have been unsure of a GLAM’s Open Access Scope, we have selected ‘some eligible data’ but we welcome corrections on this (and any other) aspect of the Survey.

Here is the overall picture of Open Access Scope from the Survey today:

Conclusion

Research conducted for the Open GLAM Survey shows that the extent to which institutions publish their eligible data on open access terms varies hugely and that it is hard to measure. Further research and tools to facilitate quantitative analysis and enable new insights would be valuable. It would also be helpful if GLAMs better documented and communicated the scope of their open access practice.

Open Access Scope is an important nuance — a detail that matters — when considering the Open GLAM landscape. It should not, however, be seen as an implicit critique of institutional policies: GLAMs that have released ‘some eligible data’ on open access terms have taken valuable first steps towards greater liberalisation.

Open access advocates within GLAMs are often limited by divergent institutional priorities, face technical barriers and lack the necessary support and resources to pursue open access in their organisation. They must be welcomed and supported to go further.