How many cultural heritage institutions make their digital collections available for free reuse? How do they do this, and where is open access most prevalent? In spring 2018,Andrea Wallace and I set out to find some answers. In the first post in a shortseries, I recount the origins and motivations of theOpen GLAM Survey.

For over a decade, the Open GLAM (Gallery, Library, Archive, Museum) movement has advocated open access to cultural heritage held in memory institutions, in order to promote the exchange of ideas and enable knowledge equity.

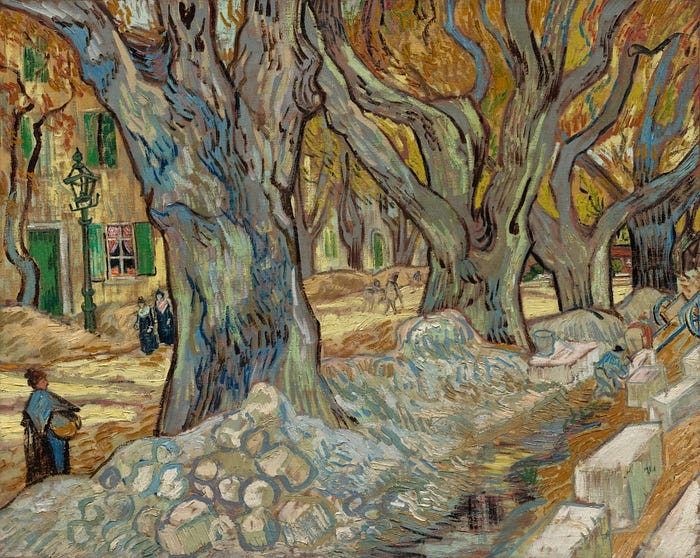

Open access has been embraced by a growing number of museums and libraries around the world, from New Zealand to Norway. So what is the global picture?

An information gap

In early 2018, despite an abundance of Open GLAM research literature, there was no single resource providing an up-to-date picture of open access policy and practice.

Spurred into action by a Twitter conversation with Simon Tanner and others, Andrea and I began wondering what such a list might look like. To us, it seemed obvious that a shared resource to see, add and update relevant information would be valuable for researchers, policymakers and cultural heritage professionals.

As well as an information gap, there seemed to be implicit bias in Open GLAM towards major European and North American institutions: the Rijksmuseum, National Gallery of Art, the British Library etc. Even if unfair, this perception risked open access being seen as something ‘just for the big Western museums’ and less relevant or accessible to smaller institutions.

Motivated to uncover the true global picture of Open GLAM, Andrea and I decided to undertake a survey.

It started with a Sheet

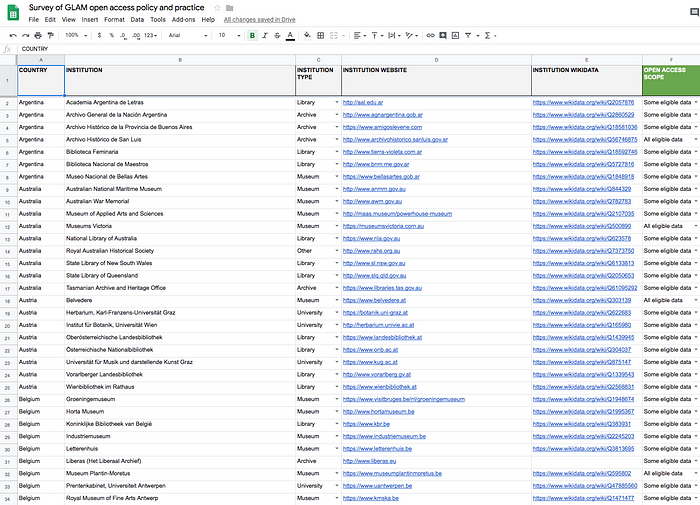

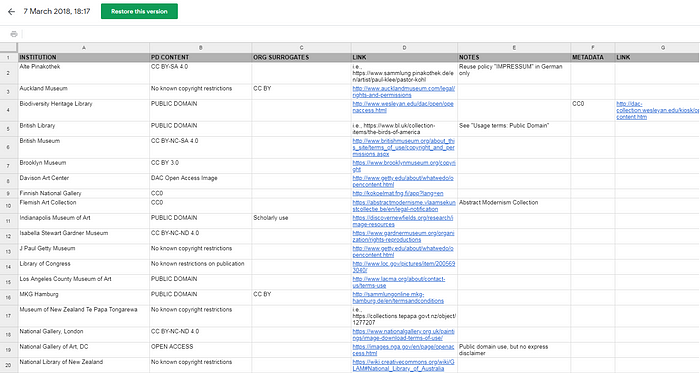

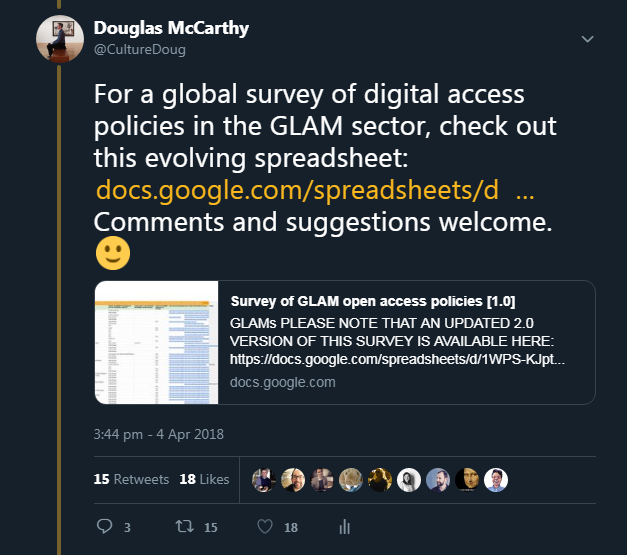

To begin, we made a simple Google Sheet listing basic information such as institution name, country, and which open licence an institution was using. With help from colleagues like David Haskiya and Sarah Powell, we had soon listed 40 or so institutions.

The precise meaning of ‘open’ sometimes lacks consensus; it’s often self-designated and rather opaque. The Survey’s working definition of ‘open’ follows Open Knowledge International’s Open Definition and its spectrum of conformant legal tools. It also considers data published under the No Known Copyright statement, developed by https://rightsstatements.org, and the Flickr Commons ‘no known copyright restrictions’ statement to be eligible (though the survey’s authors acknowledge the opacity of the latter).

‘Open means anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose.’ The Open Definition

Licences with non-commercial and/or no derivatives reuse restrictions are ineligible for inclusion in the Survey. (In-copyright material is, naturally, out of scope.)

The scope of the Survey

The chief focus of the Survey is on digital surrogates of objects in the public domain, where any term of copyright for the material object has expired or never existed in the first place. The Survey covers objects and data that GLAMs make available on their own websites and on external platforms like Wikimedia Commons, Europeana, the German Digital Library and Github.

Acorn → oak tree

Armed with a clear structure, scope and the Open Definition, Andrea and I accelerated our outreach to the global GLAM community; mostly via Twitter (it’s proven to be an excellent crowdsourcing tool).

The positive response to the Survey encouraged us to keep going. Helpful input via Twitter, email and direct comments in the Google Sheet have meant that the Survey is regularly updated with new institutions and information.

We’ve also taken advantage of online resources and communities like Flickr Commons and Coding Da Vinci. Querying Europeana data using its APIs (thanks, Jolan Wuyts) uncovered many instances of open access on a smaller, but no less valuable, scale.

Since the Survey’s prototype phase, we’ve increased its sophistication by adding direct links to data sources, APIs and Github repositories. We list Wikidata items for every institution, when available.

A year since we started the Survey, more than 550 institutions from around the world are listed, spanning several continents, many languages and a wide spectrum of institution types. The true global picture of Open GLAM is beginning to emerge.

Explore the Open GLAM Survey