Katsushika Hokusai died 170 years ago

At the height of his career, at the age of 70, he started a series of woodblock prints called Fugaku sanjūrokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji), which included the famous Kanagawa oki nami ura (Under the Wave off Kanagawa), popularly known as ‘The Great Wave’.

Around five thousand impressions from Hokusai’s series were printed and priced affordably: in 1842, the price of one sheet was fixed at 16 mon, approximately the cost of two portions of noodles.

A world before copyright

During the lifetime of Hokusai, copyright legislation did not exist in Japan. Some anti-piracy measures were in place, however.

Honyo nakama (bookshop guilds) were created in Edo, Kyoto and Osaka during the 18th century, with nakami ginmi (guild examiners) capable of police and prosecuting unauthorised reproductions of printed works. Their aim was to regulate works’ manufacture and dissemination – not to safeguard creators’ rights.

John Fiorillo explains:

‘Publishers (hanmoto) or publisher-booksellers (honya) owned woodblocks, not artists, and so the publishers could do as they pleased with the blocks without any involvement of the artist… this principle of ownership was called zôhan (possession of blocks), which implied copyright, ownership of the blocks, and the legal right to publish images or texts from the blocks.’

Great Waves around the world

Today, print impressions of ‘The Great Wave’, each one subtly different in colour and tone, can be found in museum collections around the world (in fact, some institutions have several).

When museums digitise their collections and put them online, they take a range of approaches to copyright and licensing the digital surrogates they have created. While some museums adopt open access policies to encourage the reuse and sharing of material, most choose to use copyright to regulate and monetise their digital images.

So how do museums holding an impression of Hokusai’s iconic work make it available? To find out, let’s compare fourteen cultural institutions that have digitised and published their ‘Great Wave’ online.

Rights statements

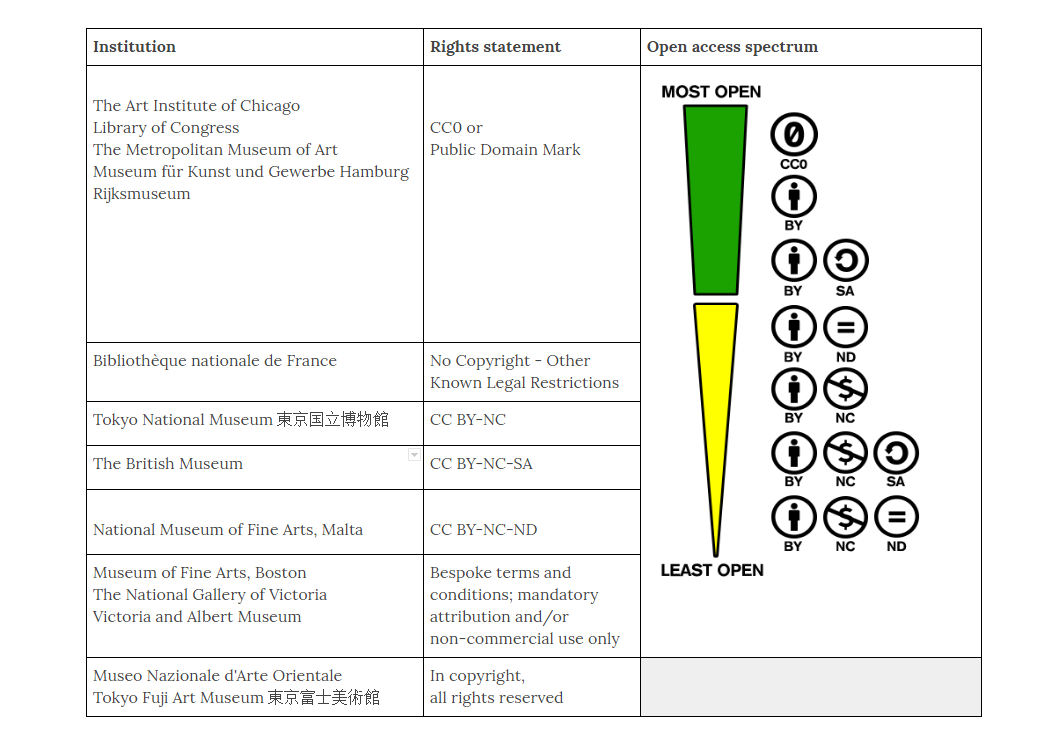

Rights statements govern, to a great extent, what one can or cannot do with a digital object. To communicate this to users, a growing number of museums are using standardised legal tools from Creative Commons and RightsStatements.org to label their digital collections.

Here are the rights statements that our fourteen institutions apply to ‘The Great Wave’, on a spectrum from the most to the least open:

Several museums have adopted the Public Domain Mark or the CC0 dedication to allow the use of ‘The Great Wave’ entirely without restriction. Some use Creative Commons licences with share-alike (SA), non-commercial (NC) and/or no-derivative (ND) limitations. Other institutions, such as The National Gallery of Victoria and The Victoria and Albert Museum, have bespoke terms of use which prospective image users must read and follow.

Image size

There are other significant considerations when it comes to using images. For example, the dimensions of a digital image dictate how large it can be printed. They also determine the level of detail which a researcher may zoom into and study.

When we compare the dimensions of the biggest ‘The Great Wave’ image available for download from our sample group of museums, a broad spe

ctrum is evident:

The Library of Congress provides the biggest downloadable image, a TIFF file measuring 8630 x 5920 pixels (51.1 megapixels), followed by the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in descending order. Most of the other institutions surveyed offer images within the range of 1–6 megapixels.

Customer journeys

For users wishing to access and use museum collections, rights statements and image size are very important. But beyond those factors, what quality of customer journey does the museum provide? How easy is it for a user to acquire a digital image? Are there forms to be filled in, or boxes to be ticked? Do you have register before you can download the content, and must you consent to the museum’s terms of use?

If we consider the customer journey of acquiring a digital image of ‘The Great Wave’ from our fourteen museums, a definite trend emerges — the more open the policy of a museum is, the easier it is to obtain its pictures.

Like the other open access institutions in our sample group, The Art Institute of Chicago’s collections website makes the process incredibly simple: clicking once on the download icon triggers the download of a high-resolution image.

In contrast, undertaking the same process on the British Museum’s website entails mandatory user registration and the submission of personal data.

After completing a registration form, the user is informed that the image request is pending and that ‘You will receive an email within two working days’. (My research experience was receiving an image of ‘The Great Wave’ by email within 24 hours of making the request.)

Given the waiting period, one presumes that each image request is reviewed and processed manually by British Museum staff.

21st century zôhan

If we adopt an economist’s perspective, we can say that a high-resolution image of ‘The Great Wave’ from a cultural institution is not a scarce commodity in the market of today’s internet: it’s a free resource.

As we’ve seen from our sample group of museums, there are several suppliers of high-quality and freely reusable digital images. ‘Trade’ with these institutions has low transactional costs for both users (fast, easy) and the institutions (automated), to their mutual benefit.

In this context, the administrative burdens, copyright restrictions and lower-quality material that characterise the non-open museums in our sample group seem markedly uncompetitive. It’s as if these institutions have unconsciously revived the concept of zôhan (possession of blocks) for the 21st century.

Such closed policies and cumbersome methods seem counterproductive for organisations whose task is to make their collections accessible to the widest possible public. To quote Merete Sanderhoff:

‘Continuing to restrict use of our reproductions once they exist in digital format means effectively cutting off the majority of users out there… If it’s difficult and/or expensive to get images of artworks from museums, people look for them elsewhere.’

Coda: reuse, remix [repeat]

Absorbing artistic influences and remixing them into new works is the lifeblood of culture. As early as 1866, Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave’ may have influenced Claude Monet’s painting The Green Wave (Monet was a keen collector of Japanese prints).

More recently, creative people have been busy remixing ‘The Great Wave’: it has been rendered in LEGO, populated with surfing cats, transformed into a quilt, and vectorized.

As illustrated by this comparative study of ‘The Great Wave’, there is a significant gulf in content quality, degrees of open access and customer experience between museums today.

Cultural institutions that wish to be relevant to online audiences, and competitive with the offer of their peers, must provide efficient and open access – when culturally appropriate – to their digital collections.

Sources and further reading

- Alexander, Isabella (2010), Copyright Law and the Public Interest in the Nineteenth Century, Hart Publishing

- Department of Asian Art (2003). Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–

- Fiorillo, John (2005). Viewing Japanese Prints

- Ganea/Heath/Saito (eds, 2005). Japanese Copyright Law: Writings in Honour of Gerhard Schricker. Kluwer Law International B.V.

- Guth, Christine M.E., Hokusai’s Great Wave: Biography of a Global Icon, University of Hawai’i Press

- Helmreich, Stefan (2015), Hokusai’s Great Wave Enters the Anthropocene, Environmental Humanities, vol. 7.

- MacGregor, Neil (2010), A History of the World in 100 Objects: Hokusai’s The Great Wave, BBC Radio 4; British Museum

- McCarthy, Douglas (April 16, 2019), Licensing policy and practice in Open GLAM, Medium

- McCarthy and Wallace (2018-), Survey of GLAM open access policy and practice, Google Sheets

- Sanderhoff, Merete (March 6, 2017), Open access can never be bad news, Medium

- Schilling, Christiaan (2016). The Representation of the Hokusai Style in Ehon Saishiki Tsū

Special thanks toDr. Andrea Wallace for reviewing this manuscript.